The Overdose Crisis

The US Centers for Disease Control reports, using provisional data available for analysis on July 6, 2025, that in calendar year 2024 at least 80,719 people in the US are reported to have died from drug overdose and toxins in the unregulated drug supply. These provisional data are incomplete and the CDC predicts that the final number of deaths in the US due to overdose and toxins in the unregulated drug supply in calendar year 2024 will be 81,740.

- In the 12-month period ending January 31, 2025, at least 78,594 people in the US were reported to have died from drug overdose and toxins in the unregulated drug supply. The CDC predicts that the final number of overdose deaths in that period will be 79,929.

- In calendar year 2023, at least 106,881 people in the US were reported to have died from drug overdose and toxins in the unregulated drug supply. The CDC predicts that the final number of overdose deaths in calendar year 2023 will be 108,550.

- In calendar year 2022, at least 109,413 people in the US were reported to have died from drug overdose and toxins in the unregulated drug supply. The CDC predicts that the final number of overdose deaths in calendar year 2022 will be 110,942.

- In calendar year 2021, at least 107,573 people in the US were reported to have died from drug overdose and toxins in the unregulated drug supply. The CDC predicts that the final number of overdose deaths in calendar year 2021 will be 109,099.

Source: Ahmad FB, Cisewski JA, Rossen LM, Sutton P. Provisional drug overdose death counts. Centers for Disease Control, National Center for Health Statistics. 2025. Last accessed July 24, 2025.

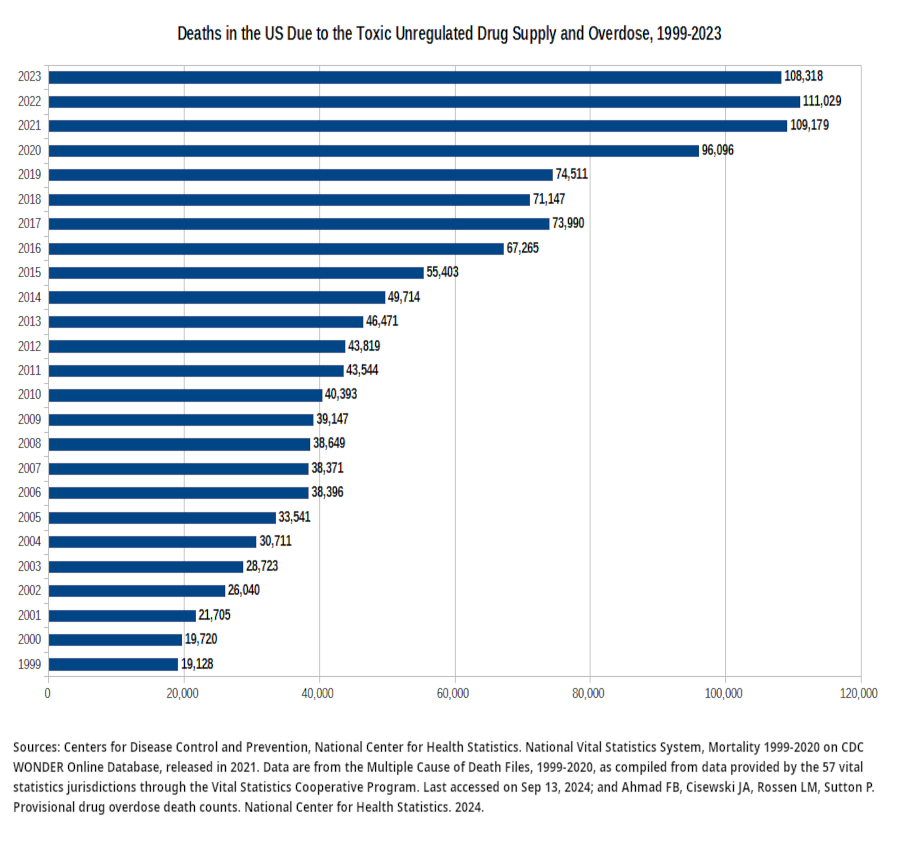

1. Deaths in the US Due to the Toxic Unregulated Drug Supply and Overdose, 1999-2023 |

| 2. Deaths in the US in 2022 Due to a Toxic Unregulated Drug Supply and Overdose "● In 2022, 107,941 drug overdose deaths occurred, resulting in an age-adjusted rate of 32.6 deaths per 100,000 standard population (Figure 1). "● Overall, the age-adjusted rate of drug overdose deaths nearly quadrupled from 8.2 in 2002 to 32.6 in 2022; however, the rate did not significantly change between 2021 (32.4) and 2022 (32.6). "● Between 2021 and 2022, the age-adjusted rate of drug overdose deaths for males increased 1.1% from 45.1 to 45.6, while the rate for females decreased 1.0% from 19.6 to 19.4, although this decrease was not significant. Spencer MR, Garnett MF, Miniño AM. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 2002–2022. NCHS Data Brief, no 491. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2024. DOI: dx.doi.org/10.15620/cdc:135849 |

| 3. Emergency department visits and trends related to cocaine in the US, 2008–2018 "Cocaine-related ED visits were predominately made by individuals who were older, male, and Black. Potential reasons include differences in drug supply, disparities in comorbidities, socioeconomic disadvantage, and other factors related to structural racism that can affect health and healthcare access [41, 42]. Complications from cocaine use are disproportionately higher in Black communities, where rates of cocaine-related deaths are comparable to the rates of opioid-related deaths in white individuals [41]. Yet cocaine-related harms have been understudied in recent years. This is alarming given overdose deaths in Black individuals are rising faster compared to whites [43, 44], and in our study, cocainerelated visits were as likely to result in admission as opioid-related visits. As attention toward the rising epidemic of stimulant-related deaths increases, interventions addressing stimulant use must address racial equity and pay attention to both cocaine and psychostimulant use to avoid further exacerbating racial and economic disparities [45]." Suen, L.W., Davy-Mendez, T., LeSaint, K.T. et al. Emergency department visits and trends related to cocaine, psychostimulants, and opioids in the United States, 2008–2018. BMC Emerg Med 22, 19 (2022). doi.org/10.1186/s12873-022-00573-0. |

| 4. Misinformation, Stigma, And Criminalization Prevent People From Seeking Help When Needed "A number of barriers, both social and systemic, prevent people with OUD from accessing the life-saving medications they need. Making headway against the opioid crisis will require addressing barriers related to stigma and discrimination, inadequate professional education, overly stringent regulatory and legal policies, and the fragmented systems of care delivery and financing for OUD. "The stigmatization of people with OUD is a major barrier to treatment seeking and retention. Social stigma from the general public is largely rooted in the misconception that addiction is simply the result of moral failing or a lack of self-discipline that is worthy of blame, rather than a chronic brain disease that requires medical treatment. Evidence demonstrates that social stigma contributes to public acceptance of discriminatory measures against people with OUD and to the public’s willingness to accept more punitive and less evidence-based policies for confronting the epidemic. Patients with OUD also report stigmatizing attitudes from some professionals within and beyond the health sector, further undercutting access to evidence-based treatment. The medications, particularly the agonist medications, used to treat OUD are also stigmatized. This can manifest in providers’ unwillingness to prescribe medications due to concerns about misuse and diversion and in the public’s mistaken belief that taking medication is “just substituting one drug for another.” Importantly, the rate of diversion is lower than for other prescribed medications, and it declines as the availability of medications to treat OUD increases. "Despite the mounting crisis, the health care workforce in the United States does not receive adequate, standardized education about OUD and the evidence base for medication-based treatment. This has created a shortage of providers who are knowledgeable, confident, and willing to provide medications to patients. Many rural areas are being overwhelmed by the opioid epidemic and have very few, if any, trained and licensed providers who can prescribe the medications. Misinformation and a lack of knowledge about OUD and its medications are also prevalent across the law enforcement and criminal justice systems." National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Committee on Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder; Mancher M, Leshner AI, editors. Medications for Opioid Use Disorder Save Lives. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); March 30, 2019. |

| 5. Unprecedented Increases In Overdose Mortality In First Seven Months Of 2020 "By disaggregating monthly trends, we found that unprecedented increases in overdose mortality occurred during the early months of pandemic in the United States. At the peak, overdose deaths in May 2020 were elevated by nearly 60% compared with the previous year, and the first 7 months of 2020 were overall elevated by 35% compared with the same period for 2019. To put this in perspective, if the final values through December 2020 were to be elevated by a similar margin, we would expect a total of 93,000 to 98,000 deaths to eventually be recorded for the year. Values for the remaining 5 months of 2020 have yet to be seen; however, it is very likely that 2020 will represent the largest year-to-year increase in overdose mortality in recent history for the United States." Joseph Friedman , Samir Akre , “COVID-19 and the Drug Overdose Crisis: Uncovering the Deadliest Months in the United States, January‒July 2020”, American Journal of Public Health 111, no. 7 (July 1, 2021): pp. 1284-1291. |

| 6. Changes in Synthetic Opioid Involvement in Overdose Deaths in the US and Involvement of Other Drugs in Combination "Among the 42,249 opioid-related overdose deaths in 2016, 19,413 involved synthetic opioids, 17,087 involved prescription opioids, and 15,469 involved heroin. Synthetic opioid involvement in these deaths increased significantly from 3007 (14.3% of opioid-related deaths) in 2010 to 19,413 (45.9%) in 2016 (P for trend <.01). Significant increases in synthetic opioid involvement in overdose deaths involving prescription opioids, heroin, and all other illicit or psychotherapeutic drugs were found from 2010 through 2016 (Table). "Among synthetic opioid–related overdose deaths in 2016, 79.7% involved another drug or alcohol. The most common co-involved substances were another opioid (47.9%), heroin (29.8%), cocaine (21.6%), prescription opioids (20.9%), benzodiazepines (17.0%), alcohol (11.1%), psychostimulants (5.4%), and antidepressants (5.2%) (Figure)." Jones CM, Einstein EB, Compton WM. Changes in Synthetic Opioid Involvement in Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States, 2010-2016. JAMA. 2018;319(17):1819–1821. |

| 7. Public Health Crisis from Acute Drug Toxicity Fatalities "Since the Early 2000s, Canada and the United States have been experiencing an unprecedented public health crisis from acute drug toxicity fatalities (“drug death crisis”) that is estimated to have claimed well beyond 1 million lives. Although initially driven mostly by fatalities from potent prescription opioids, over the past decade this crisis has changed to being propelled mostly by highly potent and toxic illicit/synthetic opioids (ISOs; e.g., fentanyl and analogues) (Ciccarone, 2021; Fischer, 2023). In 2021, Canada recorded 8,006 opioid-toxicity deaths, for an age-adjusted rate of 21.2/100,000 population (Federal, Provincial, and Territorial Special Advisory Committee on the Epidemic of Opioid Overdoses, 2023). During the same year, there were 106,699 drug overdose deaths (32.4/100,000) in the United States (Spencer et al., 2022). Although this death toll in absolute numbers and rates is even graver in the United States than in Canada, it has been shown to adversely affect life expectancy in both countries. "In Canada, comprehensive intervention efforts have been implemented and expanded over time to address this drug death crisis. These have included, for example, extensive scale-up of supervised consumption (or “overdose prevention”) services, naloxone distribution (for opioid overdose reversal), and treatment availability (including different opioid agonist therapy [OAT] formulations/modalities) for opioid use disorder (OUD) (Antoniou et al., 2020; Kennedy et al., 2022; Papamihali et al., 2020; Piske et al., 2020). These measures, however, have not been able to stem the rising tide of drug deaths. The levels of drug toxicity deaths in Canada have continuously increased (up to and including 2021), and more recent indicators suggest no significant changes moving forward (Federal, Provincial, and Territorial Special Advisory Committee on the Epidemic of Opioid Overdoses, 2023)." Benedikt Fischer and Tessa Robinson. “Safer Drug Supply” Measures in Canada to Reduce the Drug Overdose Fatality Toll: Clarifying Concepts, Practices and Evidence Within a Public Health Intervention Framework. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 2023 84:6 , 801-807. |

| 8. New York City Opens First Legally Authorized Safe Consumption Sites In US On November 30, 2021, the Office of the Mayor of the City of New York announced that "the first publicly recognized Overdose Prevention Center (OPC) services in the nation have commenced in New York City. OPCs are an extension of existing harm reduction services and will be co-located with previously established syringe service providers." According to the release: "Additionally, OPCs are a benefit to their surrounding communities, reducing public drug use and syringe litter. Other places with OPCs have not seen an increase in crime, even over many years. "OPCs will be in communities based on health need and depth of program experience. A host of City agencies will run joint operations focused on addressing street conditions across the City, and we will include an increased focus on the areas surrounding the OPCs as they open." Office of the Mayor of the City of New York, "Mayor de Blasio Announces Nation's First Overdose Prevention Center Services to Open in New York City," City of New York, NY, Nov. 30, 2021. |

| 9. Drug Poisoning Deaths In The US, 2019 "In 2019, 70,630 deaths from the toxic effects of drug poisoning (drug overdose) occurred in the United States (1), a 4.8% increase compared with 2018 and the highest recorded number in recent history." Miniño AM, Hedegaard H. Drug poisoning mortality, by state and by race and ethnicity: United States, 2019. NCHS Health E-Stats. Centers for Disease Control, National Center for Health Statistics, 2021. |

| 10. Spread of Illegally Manufactured Fentanyl in the US "Historically, there have been a number of US overdose events where a fentanyl was implicated [14▪▪,15▪]. However, the wave of overdose deaths attributed to illicit fentanyls since 2013 is unprecedented. The current rise of fentanyls is considered a positive supply shock, i.e., a supply driven more than demand-driven event [16]. Evidence for this includes: fentanyls are generally sold as ‘heroin’ i.e., fentanyl-adulterated or substituted heroin (FASH) [17,18]; wholesale distribution of FASH [19] and related overdose is regionally distributed with the Northeast and Midwest most affected followed by the South [20–22]; these are illicit products not diverted pharmaceuticals [19]; early on there was mixed desirability for FASH [17,18,23,24]; and there is market incentive in that dose-for-dose fentanyl is cheaper to produce than heroin [3,25]. The reasons why fentanyls were introduced during the current surge is complex; one argument, based on prior episodes, is that they replace heroin during periods of relative shortage [16,26]. In The Future of Fentanyl and other Synthetic Opioids, Pardo et al. highlight a confluence of supply side factors to explain the rise of fentanyls, e.g., more-efficient synthesis methods, internet communication and commerce, and out-paced regulatory environments in source countries e.g. China [27▪▪]. "The fentanyls problem is spreading. Globally, fentanyls have been detected or implicated in deaths in Europe, esp. Estonia, Latvia, and Sweden [27▪▪]. Canada has been particularly hard hit by fentanyl-related overdose [28]. The spread of fentanyls is also happening in the USA. From 2014 to 2017, the fentanyls problem was initially regionally isolated to the US Northeast and Midwest, followed to a lesser degree in the South [20,22]. However, from 2017 to 2018 the region that had the highest relative change in overdose rates due to synthetic opioids was the West [5▪]. Examining CDC data, Shover and colleagues found the share of US synthetic opioid overdose deaths attributable to seven western jurisdictions more than tripled from 2017 to 2019 [29▪▪]. Supply side data also support increasing fentanyls supply, esp. in the form of counterfeit pills, to the West [30]. And the supply is diversifying from China and Mexico to include India as a source country [31▪]." Ciccarone, Daniel. The rise of illicit fentanyls, stimulants and the fourth wave of the opioid overdose crisis. Current Opinion in Psychiatry 34(4):p 344-350, July 2021. | DOI: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000717 |

| 11. Deaths in the US in 2022 Involving Cocaine or Stimulants "● The age-adjusted rate of drug overdose deaths involving cocaine increased slightly from 1.6 deaths per 100,000 standard population in 2002 to 2.5 in 2006, decreased to 1.3 in 2010, then increased to 8.2 in 2022; the rate in 2022 was 12.3% higher than the rate in 2021 (7.3) (Figure 5). "● The age-adjusted rate of drug overdose deaths involving psychostimulants with abuse potential (subsequently, psychostimulants), which includes methamphetamine, amphetamine, and methylphenidate, was 4.0% higher in 2022 than the rate in 2021 (10.4 compared with 10.0). "● The age-adjusted rate of drug overdose deaths involving psychostimulants increased more than 34 times from 2002 (0.3) to 2022 (10.4), with different rates of change over time." Spencer MR, Garnett MF, Miniño AM. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 2002–2022. NCHS Data Brief, no 491. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2024. DOI: dx.doi.org/10.15620/cdc:135849 |

| 12. Growth of Fentanyl Related Deaths in the US "Preliminary estimates of U.S. drug overdose deaths exceeded 60,000 in 2016 and were partially driven by a fivefold increase in overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids (excluding methadone), from 3,105 in 2013 to approximately 20,000 in 2016 (1,2). Illicitly manufactured fentanyl, a synthetic opioid 50–100 times more potent than morphine, is primarily responsible for this rapid increase (3,4). In addition, fentanyl analogs such as acetylfentanyl, furanylfentanyl, and carfentanil are being detected increasingly in overdose deaths (5,6) and the illicit opioid drug supply (7). Carfentanil is estimated to be 10,000 times more potent than morphine (8). Estimates of the potency of acetylfentanyl and furanylfentanyl vary but suggest that they are less potent than fentanyl (9). Estimates of relative potency have some uncertainty because illicit fentanyl analog potency has not been evaluated in humans." Julie K. O’Donnell, PhD; John Halpin, MD; Christine L. Mattson, PhD; Bruce A. Goldberger, PhD; R. Matthew Gladden, PhD. Deaths Involving Fentanyl, Fentanyl Analogs, and U-47700 — 10 States, July–December 2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Vol. 66. Centers for Disease Control. October 27, 2017. |

| 13. Decriminalization and Deaths from a Toxic Unregulated Drug Supply and Overdose "Oregon and Washington have recently made changes to their drug laws to fully or partially legalize possession of small amounts of drugs and increase investment in treatment access. To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the association between those changes and fatal drug overdose. Using the synthetic control method to compare post-drug policy changes in fatal drug overdose rates in Oregon and Washington and estimated rates in the absence of these drug policy changes, we found no evidence that either Measure 110 in Oregon or the Washington Blake decision and subsequent legislative amendments were associated with changes in fatal drug overdose rates in either state. These findings were also robust to variations in the donor pool and the modeling strategy." Joshi S, Rivera BD, Cerdá M, et al. One-Year Association of Drug Possession Law Change With Fatal Drug Overdose in Oregon and Washington. JAMA Psychiatry. Published online September 27, 2023. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.3416 |

| 14. Routes of Administration and Deaths from Toxic Drug Supply and Drug Overdose "From January–June 2020 to July–December 2022, the number of overdose deaths with evidence of smoking doubled, and the percentage of deaths with evidence of smoking increased across all geographic regions. By late 2022, smoking was the predominant route of use among drug overdose deaths overall and in the Midwest and West regions. Increases were most pronounced when IMFs were detected, with or without stimulants. Increases in the number and percentage of deaths with evidence of smoking, and the corresponding decrease in those with evidence of injection, might be partially driven by 1) the transition from injecting heroin to smoking IMFs [Illicitly Manufactured Fentanyl] (3,4), 2) increases in deaths co-involving IMFs and stimulants that might be smoked†††† (1), and 3) increases in the use of counterfeit pills, which frequently contain IMFs and are often smoked (7). Motivations for transitioning from injection to smoking include fewer adverse health effects (e.g., fewer abscesses), reduced cost and stigma, sense of more control over drug quantity consumed per use (e.g., smoking small amounts during a period versus a single injection bolus), and a perception of reduced overdose risk among persons who use drugs (3,5,8). These motivations might also signify lower barriers for initiating drug use by smoking, or for transitioning from ingestion to smoking; compared with ingestion, smoking can intensify drug effects and increase overdose risk (9). Despite some risk reduction associated with smoking compared with injection (e.g., fewer bloodborne infections), smoking carries substantial overdose risk because of rapid drug absorption (5,9). "Nearly 80% of overdose deaths with evidence of smoking had no evidence of injection; persons who use drugs by smoking but do not inject drugs might not use traditional syringe services programs where harm reduction messaging and supplies are often provided. In response, some jurisdictions have adapted harm reduction services to provide safer smoking supplies or established health hubs to expand reach to persons using drugs through noninjection routes.§§§§ In addition, harm reduction services (e.g., peer outreach and provision of fentanyl test strips for testing drug products and naloxone to reverse opioid overdoses), messaging specific to smoking drugs, and linkage to treatment for substance use disorders can be integrated into other health care delivery (e.g., emergency departments) and public safety (e.g., drug diversion) settings. "The percentage and number of deaths with evidence of injection decreased across regions and drug categories. Observed decreases might reflect transitions to noninjection routes and response to public health efforts to reduce injection drug use because of its risk for overdose and infectious disease transmission (3,4,10). Despite these declines, more than 4,000 drug overdose deaths had evidence of injection during July–December 2022. Syringe services programs help to engage persons who use drugs in services (10); sustained efforts to provide sterile injection supplies, additional harm reduction tools, and linkage to treatment for substance use disorders, including medications for opioid use disorder, are important for further reduction in the number of overdose deaths from injection drug use. Lessons learned from implementing syringe services programs could be applied to other harm reduction and outreach models to reach more persons who use drugs by any route." Tanz LJ, Gladden RM, Dinwiddie AT, et al. Routes of Drug Use Among Drug Overdose Deaths — United States, 2020–2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2024;73:124–130. DOI: dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7306a2 |

| 15. Co-Involvement of Stimulants and Fentanyl in Drug-Related Deaths in the US, 2010-2021 "Findings "The percent of US overdose deaths involving both fentanyl and stimulants increased from 0.6% (n = 235) in 2010 to 32.3% (34 429) in 2021, with the sharpest rise starting in 2015. In 2010, fentanyl was most commonly found alongside prescription opioids, benzodiazepines, and alcohol. In the Northeast this shifted to heroin-fentanyl co-involvement in the mid-2010s, and nearly universally to cocaine-fentanyl co-involvement by 2021. Universally in the West, and in the majority of states in the South and Midwest, methamphetamine-fentanyl co-involvement predominated by 2021. The proportion of stimulant involvement in fentanyl-involved overdose deaths rose in virtually every state 2015–2021. Intersectional group analysis reveals particularly high rates for older Black and African American individuals living in the West. "Conclusions "By 2021 stimulants were the most common drug class found in fentanyl-involved overdoses in every state in the US. The rise of deaths involving cocaine and methamphetamine must be understood in the context of a drug market dominated by illicit fentanyls, which have made polysubstance use more sought-after and commonplace. The widespread concurrent use of fentanyl and stimulants, as well as other polysubstance formulations, presents novel health risks and public health challenges." Friedman, J, Shover, CL. Charting the fourth wave: Geographic, temporal, race/ethnicity and demographic trends in polysubstance fentanyl overdose deaths in the United States, 2010–2021. Addiction. 2023. doi.org/10.1111/add.16318 |

| 16. Key Factors Underlying Increasing Rates of Heroin Use and Opioid Overdose in the US "A key factor underlying the recent increases in rates of heroin use and overdose may be the low cost and high purity of heroin.45,46 The price in retail purchases has been lower than $600 per pure gram every year since 2001, with costs of $465 in 2012 and $552 in 2002, as compared with $1237 in 1992 and $2690 in 1982.45 A recent study showed that each $100 decrease in the price per pure gram of heroin resulted in a 2.9% increase in the number of hospitalizations for heroin overdose.46" Wilson M. Compton, M.D., M.P.E., Christopher M. Jones, Pharm.D., M.P.H., and Grant T. Baldwin, Ph.D., M.P.H. Relationship between Nonmedical Prescription-Opioid Use and Heroin Use. N Engl J Med 2016; 374:154-163. January 14, 2016. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra1508490. |

| 17. Association of Dose Tapering With Overdose or Mental Health Crisis Among Patients Prescribed Long-term Opioids "In a large cohort of patients in the US prescribed stable, longterm, higher-dose opioids, undergoing opioid dose tapering was associated with statistically significant risk of subsequent overdose and mental health crisis, including suicidality." Agnoli A, Xing G, Tancredi DJ, Magnan E, Jerant A, Fenton JJ. Association of Dose Tapering With Overdose or Mental Health Crisis Among Patients Prescribed Long-term Opioids. JAMA. 2021;326(5):411–419. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.11013 |

| 18. Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths in the US 2017-2018 "Of the 70,237 drug overdose deaths in the United States in 2017, approximately two thirds (47,600) involved an opioid (1). In recent years, increases in opioid-involved overdose deaths have been driven primarily by deaths involving synthetic opioids other than methadone (hereafter referred to as synthetic opioids) (1). CDC analyzed changes in age-adjusted death rates from 2017 to 2018 involving all opioids and opioid subcategories* by demographic characteristics, county urbanization levels, U.S. Census region, and state. During 2018, a total of 67,367 drug overdose deaths occurred in the United States, a 4.1% decline from 2017; 46,802 (69.5%) involved an opioid (2). From 2017 to 2018, deaths involving all opioids, prescription opioids, and heroin decreased 2%, 13.5%, and 4.1%, respectively. However, deaths involving synthetic opioids increased 10%, likely driven by illicitly manufactured fentanyl (IMF), including fentanyl analogs (1,3)." Wilson N, Kariisa M, Seth P, Smith H 4th, Davis NL. Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths - United States, 2017-2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(11):290‐297. Centers for Disease Control. Published 2020 Mar 20. |

| 19. Drugs Most Frequently Involved in Drug Overdose Deaths in the US 2011–2016 "The percentage of deaths with concomitant involvement of other drugs varied by drug. For example, almost all drug overdose deaths involving alprazolam or diazepam (96%) mentioned involvement of other drugs. In contrast, 50% of the drug overdose deaths involving methamphetamine, and 69% of the drug overdose deaths involving fentanyl mentioned involvement of one or more other specific drugs. "Table D shows the most frequent concomitant drug mentions for each of the top 10 drugs involved in drug overdose deaths in 2016. " Two in five overdose deaths involving cocaine also mentioned fentanyl. " Nearly one-third of drug overdose deaths involving fentanyl also mentioned heroin (32%). " Alprazolam was mentioned in 26% of the overdose deaths involving hydrocodone, 22% of the deaths involving methadone, and 25% of the deaths involving oxycodone. " More than one-third of the overdose deaths involving cocaine also mentioned heroin (34%). " More than 20% of the overdose deaths involving methamphetamine also mentioned heroin." Hedegaard H, Bastian BA, Trinidad JP, Spencer M, Warner M. Drugs most frequently involved in drug overdose deaths: United States, 2011–2016. National Vital Statistics Reports; vol 67 no 9. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2018. |

| 20. Retail Price of Heroin in the US, Canada, and the UK Retail Prices of Heroin (US$) United States (2019): Canada (2018): UK (2021): UN Office on Drugs and Crime. World Drug Report 2024: Statistical Annex. Table 8.1: Prices and Purities of Drugs, accessed April 22, 2025. |

| 21. Drugs Most Frequently Mentioned in Overdose Deaths in the US 2011-2016 "The number of drug overdose deaths per year increased 54%, from 41,340 deaths in 2011 to 63,632 deaths in 2016 (Table A). From the literal text analysis, the percentage of drug overdose deaths mentioning at least one specific drug or substance increased from 73% of the deaths in 2011 to 85% of the deaths in 2016. The percentage of drug overdose deaths that mentioned only a drug class but not a specific drug or substance declined from 5.1% of deaths in 2011 to 2.5% in 2016. Review of the literal text for these deaths indicated that the deaths that mentioned only a drug class frequently involved either an opioid or an opiate (ranging from 54% in 2015 to 60% in 2016). The percentage of deaths that did not mention a specific drug or substance or a drug class declined from 22% of drug overdose deaths in 2011 to 13% in 2016." Hedegaard H, Bastian BA, Trinidad JP, Spencer M, Warner M. Drugs most frequently involved in drug overdose deaths: United States, 2011–2016. National Vital Statistics Reports; vol 67 no 9. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2018. |

| 22. Drugs Most Frequently Involved in Drug Overdose Deaths in the US 2011–2016 "For the top 15 drugs: " Among drug overdose deaths that mentioned at least one specific drug, oxycodone ranked first in 2011,heroin from 2012 through 2015, and fentanyl in 2016. " In 2011 and 2012, fentanyl was mentioned in approximately 1,600 drug overdose deaths each year, but mentions increased in 2013 (1,919 deaths),2014 (4,223 deaths), 2015 (8,251 deaths), and 2016(18,335 deaths). In 2016, 29% of all drug overdose deaths mentioned involvement of fentanyl. " The number of drug overdose deaths involving heroin increased threefold, from 4,571 deaths or 11% of all drug overdose deaths in 2011 to 15,961 deaths or 25% of all drug overdose deaths in 2016. " Throughout the study period, cocaine ranked second or third among the top 15 drugs. From 2014 through 2016, the number of drug overdose deaths involving cocaine nearly doubled from 5,892 to 11,316. " The number of drug overdose deaths involving methamphetamine increased 3.6-fold, from 1,887 deaths in 2011 to 6,762 deaths in 2016. " The number of drug overdose deaths involving methadone decreased from 4,545 deaths in 2011 to 3,493 deaths in 2016." Hedegaard H, Bastian BA, Trinidad JP, Spencer M, Warner M. Drugs most frequently involved in drug overdose deaths: United States, 2011–2016. National Vital Statistics Reports; vol 67 no 9. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2018. |

| 23. Rescue Breathing and Naloxone in Response to Overdose "Relevant literature on overdose response included 3 clinical guidelines,1,21,32 3 grey literature reports (a rapid review,36 an evidence brief37 and a report of a technical working group on resuscitation training38), and a pilot and feasibility study.39 The conclusions in these resources differ on overdose response, notably on the role of rescue breathing and the order in which resuscitation steps occur. An in-depth discussion of the literature is available in Appendix 1, and Appendix 3 contains more detail on findings and included studies. "As the mandate of THN [Take Home Naloxone] programs includes overdose response training, our recommendation focuses on trained overdose response. Evidence from the Naloxone Guidance Development Group indicates that community overdose responders are effectively trained through different methods. For the purposes of this document, we recognize that people using THN programs may be trained on overdose response through their peers, using online resources, THN programs or cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) training courses. "In the literature, multiple sources identified naloxone administration and calling 911 or other emergency response numbers as critical steps in overdose response.1,21,32,36,38,39 Three guidance documents included verbal and physical stimulation to assess whether someone is experiencing overdose and to stimulate breathing.21,32,38 "For a responder trained in overdose response, guidance may differ according to whether the responder suspects respiratory depression or cardiac arrest. Overdose response must take the pathophysiology of opioid overdose into account. When someone experiences opioid overdose, regulation of breathing is impaired, respiration is depressed and insufficient oxygen reaches the brain and other organs.1 Because the person experiencing overdose is not breathing effectively, oxygen also cannot reach the heart and the individual may experience cardiac arrest (i.e., their heart stops beating or beats too ineffectively to support their vital organs).1" Ferguson M, Rittenbach K, Leece P, et al. Guidance on take-home naloxone distribution and use by community overdose responders in Canada. CMAJ. 2023;195(33):E1112-E1123. doi:10.1503/cmaj.230128 |

| 24. Involvement of Fentanyl in Overdose Deaths in the US "Fentanyl was detected in 56.3% of 5,152 opioid overdose deaths in the 10 states during July–December 2016 (Figure). Among these 2,903 fentanyl-positive deaths, fentanyl was determined to be a cause of death by the medical examiner or coroner in nearly all (97.1%) of the deaths. Northeastern states (Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island) and Missouri** reported the highest percentages of opioid overdose deaths involving fentanyl (approximately 60%–90%), followed by Midwestern and Southern states (Ohio, West Virginia, and Wisconsin), where approximately 30%–55% of decedents tested positive for fentanyl. New Mexico and Oklahoma reported the lowest percentage of fentanyl-involved deaths (approximately 15%–25%). In contrast, states detecting any fentanyl analogs in >10% of opioid overdose deaths were spread across the Northeast (Maine, 28.6%, New Hampshire, 12.2%), Midwest (Ohio, 26.0%), and South (West Virginia, 20.1%) (Figure) (Table 1). "Fentanyl analogs were present in 720 (14.0%) opioid overdose deaths, with the most common being carfentanil (389 deaths, 7.6%), furanylfentanyl (182, 3.5%), and acetylfentanyl (147, 2.9%) (Table 1). Fentanyl analogs contributed to death in 535 of the 573 (93.4%) decedents. Cause of death was not available for fentanyl analogs in 147 deaths.†† Five or more deaths involving carfentanil occurred in two states (Ohio and West Virginia), furanylfentanyl in five states (Maine, Massachusetts, Ohio, West Virginia, and Wisconsin), and acetylfentanyl in seven states (Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Ohio, West Virginia, and Wisconsin). U-47700 was present in 0.8% of deaths and found in five or more deaths only in Ohio, West Virginia, and Wisconsin (Table 1). Demographic characteristics of decedents were similar among overdose deaths involving fentanyl analogs and fentanyl (Table 2). Most were male (71.7% fentanyl and 72.2% fentanyl analogs), non-Hispanic white (81.3% fentanyl and 83.6% fentanyl analogs), and aged 25–44 years (58.4% fentanyl and 60.0% fentanyl analogs) (Table 2). "Other illicit drugs co-occurred in 57.0% and 51.3% of deaths involving fentanyl and fentanyl analogs, respectively, with cocaine and confirmed or suspected heroin detected in a substantial percentage of deaths (Table 2). Nearly half (45.8%) of deaths involving fentanyl analogs tested positive for two or more analogs or fentanyl, or both. Specifically, 30.9%, 51.1%, and 97.3% of deaths involving carfentanil, furanylfentanyl, and acetylfentanyl, respectively, tested positive for fentanyl or additional fentanyl analogs. Forensic investigations found evidence of injection drug use in 46.8% and 42.1% of overdose deaths involving fentanyl and fentanyl analogs, respectively. Approximately one in five deaths involving fentanyl and fentanyl analogs had no evidence of injection drug use but did have evidence of other routes of administration. Among these deaths, snorting (52.4% fentanyl and 68.8% fentanyl analogs) and ingestion (38.2% fentanyl and 29.7% fentanyl analogs) were most common. Although rare, transdermal administration was found among deaths involving fentanyl (1.2%), likely indicating pharmaceutical fentanyl (Table 2). More than one third of deaths had no evidence of route of administration." Julie K. O’Donnell, PhD; John Halpin, MD; Christine L. Mattson, PhD; Bruce A. Goldberger, PhD; R. Matthew Gladden, PhD. Deaths Involving Fentanyl, Fentanyl Analogs, and U-47700 — 10 States, July–December 2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Vol. 66. Centers for Disease Control. October 27, 2017. |

| 25. American College of Medical Toxicology and the American Academy of Clinical Toxicology position statement: nalmefene should not replace naloxone as the primary opioid antidote at this time "As physicians, pharmacists, scientists, and specialists in poison information, we are experts in pharmacology, toxicology, and the management of opioid overdose and addiction. We applaud the effort to seek out new therapeutic strategies for the management of these patients. "We are concerned that the use of a longer-acting reversal agent would not improve on current practice and could potentially cause harm. When withdrawal is precipitated by an opioid antagonist, there are few good management options. In most cases, the best strategy is to address and support the patient’s signs and symptoms until the effects of the antagonist wane. In the case of naloxone, which has a relatively short duration of action, severe withdrawal usually lasts less than an hour with symptoms typically persisting no more than 90 min [Citation25–27]. A longer-acting antagonist is anticipated to cause longer-lasting precipitated withdrawal and may lead to worse patient outcomes. Clinical experience with both naltrexone and nalmefene suggests prolonged withdrawal is a complication of longer-acting opioid antagonists [Citation28]. Although a longer-acting antagonist may be theoretically beneficial for the resuscitation of opioid-naive individuals in an opioid-induced mass casualty incident, this type of event has never been reported in North America and this application is unstudied. "We are also concerned that patients who receive nalmefene may require longer periods of observation, by up to several hours, to observe for recrudescent effects as the antagonist effects wane. Patients who receive nalmefene will still need medical observation to ensure that respiratory depression does not recur after the effects of the medication subside. This will prolong emergency department visit length and challenge patient and clinician expectations, further burdening a taxed system. Further clinical study is needed to understand whether a reduction in repeat antagonist use justifies a longer length of stay or longer period of withdrawal. "Finally, we are concerned that intranasal nalmefene has not been adequately studied for effectiveness in the actual setting and patient population: for patients with severe opioid intoxication in the out-of-hospital environment. Lack of proof of safety and efficacy in real-world use could result in significant harm if widely utilized. "The potential benefits of nalmefene over naloxone (greater opioid receptor affinity, longer duration action) carry the risk of causing harm. These benefits, if present, should be demonstrated in the clinical environment, balanced with the risks, and compared to naloxone prior to the broad adoption of nalmefene." Andrew I. Stolbach, Maryann E. Mazer-Amirshahi, Lewis S. Nelson & Jon B. Cole (2023) American College of Medical Toxicology and the American Academy of Clinical Toxicology position statement: nalmefene should not replace naloxone as the primary opioid antidote at this time, Clinical Toxicology, 61:11, 952-955, DOI: 10.1080/15563650.2023.2283391 |

| 26. Naloxone vs Nalmefene "While the addition of stronger, longer-acting opioid overdose reversal agents expands the options available to combat the fatal opioid overdose crisis, their inception is perhaps without clinical grounds. Data supports continued practice without these stronger, longer acting nalmefene agents, and it is unclear whether any benefits nalmefene offers outweigh the apparent risks of its use. Nalmefene may yet find a clinical niche, but at this time, appears to be a solution designed to resolve hypothetical complications without fully understanding the unintended consequences of use. As such, without further evidence healthcare professionals should not support the use of stronger, longer-acting opioid overdose reversal agents. Further study is necessary, before nalmefene, or other naloxone alternatives should be incorporated into general practice." Infante AF, Elmes AT, Gimbar RP, Messmer SE, Neeb C, Jarrett JB. Stronger, longer, better opioid antagonists? Nalmefene is NOT a naloxone replacement. Int J Drug Policy. 2024;124:104323. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2024.104323 |

| 27. Nalmefene vs Naloxone "As shown above, the data supports that these stronger, longer-acting agents may be unnecessary, with other research suggesting their existence may also cause undue harm. Using a stronger or longer-acting antagonist as a one-size-fits-all approach may put patients at greater risk for experiencing more severe and/or prolonged withdrawal symptoms.(Bennett et al., 2020; Hill et al., 2022; Neale & Strang, 2015) Providers may find it difficult to manage withdrawal symptoms and comorbidities like chronic pain, forcing the patient to suffer until the reversal agent wears off. It is also notable to consider how patients who are naïve to nalmefene may react upon discharge following administration. These patients may attempt to self-manage withdrawal symptoms or cravings only to find higher opioid doses are required to overcome the nalmefene blockade, increasing their propensity to overdose as was observed when patients began adjusting to naloxone.(Neale & Strang, 2015) Alternatively, patients accustomed to opioid withdrawal symptoms subsiding within 1 to 2 h after naloxone administration may not be able to tolerate several hours of withdrawal, increasing both the likelihood of attempts to overcome the blockade and resistance to using reversal agents in the future.(Neale & Strang, 2015) Considering the average layperson likely does not fully grasp the potential harm of nalmefene, and that any opioid overdose education they may have received from an opioid overdose education & naloxone distribution (OEND) program would have been naloxone and harm reduction focused, adding these agents into the market creates opportunities for greater clinical complication. This lack of familiarity combined with the lack of clinical discretionary knowledge by the layperson who may be administering these medications in the field sets the stage for nalmefene exposure to elicit prolonged agitation and negative consequences.(Brenner et al., 2021) Furthermore, it is possible that nalmefene administration may complicate the initiation of medications for opioid use disorder such as buprenorphine/naloxone, which can be done in as little as three hours following the last opioid use when co-administered with naloxone.(Randall et al., 2023) Additionally, the FDA approved intranasal naloxone for over-the-counter use in March 2023. It is yet to be seen how this will affect its insurance coverage and medication access.(Harris, 2023b) This may especially affect vulnerable patient populations such as those with limited disposable income. Coverage for prescription nalmefene may serve some relief when naloxone is not covered or attainable by other means." Infante AF, Elmes AT, Gimbar RP, Messmer SE, Neeb C, Jarrett JB. Stronger, longer, better opioid antagonists? Nalmefene is NOT a naloxone replacement. Int J Drug Policy. 2024;124:104323. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2024.104323 |

| 28. Reductions in Opioid Prescribing for People with Severe Pain "According to the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, the annual share of US adults who were prescribed opioids decreased from 12.9 percent in 2014 to 10.3 percent in 2016, and the decrease was concentrated among adults with shorter-term rather than longer-term prescriptions. The decrease was also larger for adults who reported moderate or more severe pain (from 32.8 percent to 25.5 percent) than for those who reported lessthan-moderate pain (from 8.0 percent to 6.6 percent). In the same period opioids were prescribed to 3.75 million fewer adults reporting moderate or more severe pain and 2.20 million fewer adults reporting less-thanmoderate pain. Because the decline in prescribing primarily involved adults who reported moderate or more severe pain, these trends raise questions about whether efforts to decrease opioid prescribing have successfully focused on adults who report less severe pain." Mark Olfson, Shuai Wang, Melanie M. Wall, and Carlos Blanco. Trends In Opioid Prescribing And Self-Reported Pain Among US Adults. Health Affairs 2020 39:1, 146-154. |

| 29. Xylazine and Skin Ulcers "Importantly, our results show that evidence of injection was more prevalent among decedents with xylazine and heroin and/or fentanyl detections. Despite limited literature on the health effects of chronic xylazine use, regular injection of xylazine has been associated with skin ulcers, abscesses and lesions in Puerto Rico.2 3 Semistructured interviews with people who use xylazine in Puerto Rico revealed that regular use of xylazine leads to skin ulcers.4 As skin ulcers are painful, people may continually inject at the site of the ulcer to alleviate the pain as xylazine is a potent α2-adrenergic agonist that mediates via central α2-receptors, which decreases perception of painful stimuli.1 People may self-treat the wound by draining or lancing it, which can exacerbate negative outcomes.8 While Philadelphia has seen a rise in skin and soft tissue infections relating to injection drug use, it is not yet clear whether or not this is due to increased presence of xylazine in the drug supply.9" Johnson J, Pizzicato L, Johnson C, et al. Increasing presence of xylazine in heroin and/or fentanyl deaths, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2010–2019. Injury Prevention 2021;27:395-398. |

| 30. Association of Dose Tapering With Overdose or Mental Health Crisis "In the current study, tapering was associated with absolute differences in rates of overdose or mental health crisis events of approximately 3 to 4 events per 100 person-years compared with nontapering. These findings suggest that adverse events associated with tapering may be relatively common and support HHS recommendations for more gradual dose reductions when feasible and careful monitoring for withdrawal, substance use, and psychological distress.9 "Previous research has examined adverse outcomes associated with discontinuing long-term opioids.10-14 This analysis demonstrated associations between adverse outcomes and a more sensitive indicator of opioid dose reduction (≥15% from baseline). The associations persisted in sensitivity analyses that excluded patients who discontinued opioids during follow-up, suggesting that the observed associations between tapering and overdose and mental health crisis are not entirely explained by events occurring in patients discontinuing opioids. Additionally, all categories of maximum dose reduction velocity demonstrated higher relative rates of outcomes compared with the lowest (<10% per month), suggesting that risks were not confined to patients undergoing rapid tapering. "Patients undergoing tapering from higher baseline opioid doses had higher associated risk for the study outcomes compared with patients undergoing tapering from lower baseline doses. Due to physiologic opioid tolerance,27 patients receiving higher doses may have heightened intolerance of opioid dose disruption, potentially warranting additional caution in patients tapering from higher doses." Agnoli A, Xing G, Tancredi DJ, Magnan E, Jerant A, Fenton JJ. Association of Dose Tapering With Overdose or Mental Health Crisis Among Patients Prescribed Long-term Opioids. JAMA. 2021;326(5):411–419. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.11013 |

| 31. Opioid Use for Pain Management "'Opioid' is a generic term for natural or synthetic substances that bind to specific opioid receptors in the central nervous system (CNS), producing an agonist action. Opioids are also called narcotics—a term originally used to refer to any psychoactive substance that induces sleep. Opioids have both analgesic and sleep-inducing effects, but the two effects are distinct from each other. "Some opioids used for analgesia have both agonist and antagonist actions. Potential for abuse among those with a known history of abuse or addiction may be lower with agonist-antagonists than with pure agonists, but agonist-antagonist drugs have a ceiling effect for analgesia and induce a withdrawal syndrome in patients already physically dependent on opioids. "In general, acute pain is best treated with short-acting (immediate-release) pure agonist drugs at the lowest effective dosage possible and for a short time; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines recommend 3 to 7 days (1 ). Clinicians should reevaluate patients before re-prescribing opioids for acute pain syndromes. For acute pain, using opioids at higher doses and/or for a longer time increases the risk of needing long-term opioid therapy and of having opioid adverse effects. "Chronic pain, when treated with opioids, may be treated with long-acting formulations (see tables Opioid Analgesics and Equianalgesic Doses of Opioid Analgesics ). Because of the higher doses in many long-acting formulations, these drugs have a higher risk of serious adverse effects (eg, death due to respiratory depression) in opioid-naive patients. "Opioid analgesics have proven efficacy in the treatment of acute pain, cancer pain , and pain at the end of life and as part of palliative care . They are sometimes underused in patients with severe acute pain or in patients with pain and a terminal disorder such as cancer, resulting in needless pain and suffering. Reasons for undertreatment include "Generally, opioids should not be withheld when treating acute, severe pain; however, simultaneous treatment of the condition causing the pain usually limits the duration of severe pain and the need for opioids to a few days or less. Also, opioids should generally not be withheld when treating cancer pain; in such cases, adverse effects can be prevented or managed, and addiction is less of a concern. "Duration of opioid trials for chronic pain due to disorders other than terminal disorders (eg, cancer) has been short. Thus, there is little evidence to support opioid therapy for long-term management of chronic pain due to nonterminal disorders. Also, serious adverse effects of long-term opioid therapy (eg, opioid use disorder [addiction], overdose, respiratory depression, death) are being increasingly recognized. Thus, in patients with chronic pain due to nonterminal disorders, lower-risk nonopioid therapies should be tried before opioids; these therapies include "In patients with chronic pain due to nonterminal disorders, opioid therapy may be considered, but usually only if nonopioid therapy has been unsuccessful. In such cases, opioids are used (often in combination with nonopioid therapies) only when the benefit of pain reduction and functional improvement outweighs the risks of opioid adverse effects and misuse. Obtaining informed consent may help clarify the goals, expectations, and risks of treatment and facilitate education and counseling about misuse. "Patients receiving long-term (> 3 months) opioid therapy should be regularly assessed for pain control, functional improvement, adverse effects, and signs of misuse. Opioid therapy should be considered a failed treatment and should be tapered and stopped if the following occur: "Physical dependence (development of withdrawal symptoms when a drug is stopped) should be assumed to exist in all patients treated with opioids for more than a few days. Thus, opioids should be used as briefly as possible, and in dependent patients, the dose should be tapered to control withdrawal symptoms when opioids are no longer necessary. Patients with pain due to an acute, transient disorder (eg, fracture, burn, surgical procedure) should be switched to a nonopioid drug as soon as possible. Dependence is distinct from opioid use disorder (addiction), which, although it does not have a universally accepted definition, typically involves compulsive use and overwhelming involvement with the drug, including craving, loss of control over use, and use despite harm." James C. Watson, MD, Treatment of Pain, Merck Manual Professional Version, last accessed August 31, 2021. |

| 32. Tighter Prescribing Regulations Drive Illegal Sales "The US Drug Enforcement Administration introduced a schedule change for hydrocodone combination products in October 2014. During the period of our study, October 2013 to July 2016, the percentage of total drug sales represented by prescription opioids in the US doubled from 6.7% to 13.7%, which corresponds to a yearly increase of 4 percentage points in market share. It is not possible to determine the location of buyers from cryptomarket data. We cannot know, for example, if a drug shipped from a vendor in Europe was purchased by a US customer. Nevertheless, cryptomarket users often prefer buying and selling from vendors in the same country; international shipments carry risks of loss, interception by officials, and increased delivery times. A study of cryptomarkets in Australia found that local vendors were often preferred over international counterparts, despite substantially higher prices.24 Another study36 also noted the downward trends of international sales and therefore an increase in domestic sales, and yet another study47 found that drug trading through cryptomarket is heavily constrained by offline geography. This preference for domestic trading, combined with the relatively large numbers of US drug vendors trading in cryptomarkets, leads us to presume that most sales of prescription drugs by US vendors will be sold to customers based in the US. Conversely, most transactions generated by non-US vendors will not be sold to US customers. "The results of our interrupted time series suggest the possibility of a causal relation between the schedule change and the percentage of sales represented by prescription opioids on cryptomarkets. Our analysis cannot rule out other possible causal explanatory factors, but our results are consistent with the possibility that the schedule change might have directly contributed to the changes we observed in the supply of illicit opioids. This possibility is reinforced by the fact that the increased availability and sales of prescription opioids on cryptomarkets in the US after the schedule change was not replicated for cryptomarkets elsewhere. "Our results are consistent with the possibility of demand led increases. The first increase observed for prescription opioids was for actual sales (fig 1); with increases for active listings, and then all listings, following. One explanation is that cryptomarket vendors perceived an increase in demand and responded by placing more listings for prescription opioids and thereby increasing supply. Our results are also consistent with the iron law of prohibition34 insofar as we identified the largest sales increases for more potent prescription opioids—specifically, oxycodone and fentanyl. Cryptomarkets may function as a supply gateway48: customers who initially sought out illicit hydrocodone on cryptomarkets after the schedule change might then have favoured more potent opioids available on the marketplace." Martin James, Cunliffe Jack, Décary-Hétu David, Aldridge Judith. Effect of restricting the legal supply of prescription opioids on buying through online illicit marketplaces: interrupted time series analysis. British Medical Journal. 2018; 361:k2270. |

| 33. The Burden of Opioid-Related Mortality in the United States "Over the 15-year study period, 335,123 opioid-related deaths in the United States met our inclusion criteria, with an increase of 345% from 9489 in 2001 (33.3 deaths per million population) to 42,245 in 2016 (130.7 deaths per million population). By 2016, men accounted for 67.5% of all opioid-related deaths (n = 28,496), and the median (interquartile range) age at death was 40 (30-52) years. The proportion of deaths attributable to opioids increased over the study period, rising 292% (from 0.4% [1 in 255] to 1.5% [1 in 65]), and increased steadily over time in each age group studied (P < .001 for all age groups) (Figure). The largest absolute increase between 2001 and 2016 was observed among those aged 25 to 34 years (15.8% increase from 4.2% in 2001 to 20.0% in 2016), followed by those aged 15 to 24 years (9.4% increase from 2.9% to 12.4%). However, the largest relative increases occurred among adults aged 55 to 64 years (754% increase from 0.2% to 1.7%) and those aged 65 years and older (635% increase from 0.01% to 0.07%). Despite the fact that confirmed opioid-related deaths represent a small percentage of all deaths in these older age groups, the absolute number of deaths is moderate. In 2016, 18.4% (7762 of 42,245) of all opioid-related deaths in the United States occurred among those aged 55 years and older. "In our analysis of the burden of early loss of life from opioid overdose, we found that opioid-related deaths were responsible for 1,681,359 YLL [Years of Life Lost] (5.2 YLL per 1000 population) in the United States in 2016 (Table); however, this varied by age and sex. In particular, when stratified by age, adults aged 25 to 34 years and those aged 35 to 44 years experienced the highest burden from opioid-related deaths (12.9 YLL per 1000 population and 9.9 YLL per 1000 population, respectively). We also found that the burden of opioid-related death was higher among men (1,125,711 YLL; 7.0 YLL per 1000 population) compared with women (555,648 YLL; 3.4 YLL per 1000 population). Importantly, among men aged 25 to 34 years, this rate increased to 18.1 YLL per 1000 population, and the total YLL in this population represented nearly one-quarter of all YLL in the United States in 2016 (411,805 of 1,681,359 [24.5%])." Gomes T, Tadrous M, Mamdani MM, Paterson JM, Juurlink DN. The Burden of Opioid-Related Mortality in the United States. JAMA Network Open. 2018;1(2):e180217. |

| 34. Xylazine as an Adulterant in Opioids "Harms of xylazine use in humans are not well documented, but evidence suggests that combined use of xylazine and an opioid such as fentanyl may increase the risk of overdose fatality.1 Although naloxone, the opioid overdose reversal drug, is not effective against xylazine alone, unintentional fatal overdoses with xylazine detections also had heroin and/or fentanyl detections in Philadelphia, indicating timely administration of naloxone is critical for preventing deaths. Additional treatment for xylazine poisoning may involve supportive care using intubation, ventilation and administration of intravenous fluid.1 "Of note, as fentanyl has largely replaced the heroin supply in Philadelphia, xylazine has been increasingly found in combination with fentanyl. Some evidence suggests that the combination of xylazine and fentanyl in humans may potentiate the desired effect of sedation and the adverse effects of respiratory depression, bradycardia and hypotension caused by fentanyl alone,1 comparable to the synergistic effects of combining benzodiazepines with heroin and/or fentanyl.7 While benzodiazepines were detected in 97 (58%) of the 168 unintentional overdose deaths with heroin and/or fentanyl detections in Philadelphia in 2010, this decreased to 232 (28%) of the 858 unintentional overdose deaths with heroin and/or fentanyl detections in 2019. This decline may be the result of increasing demand for xylazine among people who use drugs in Philadelphia and/or changes in the illicit drug market as drug seizure data indicate that xylazine is increasing in polydrug samples. Indeed, focus groups with people who use drugs in Philadelphia have suggested that the addition of xylazine to fentanyl “makes you feel like you’re doing dope (heroin) in the old days (before it was replaced by fentanyl)” when the euphoric effects lasted longer." Johnson J, Pizzicato L, Johnson C, et al. Increasing presence of xylazine in heroin and/or fentanyl deaths, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2010–2019. Injury Prevention 2021;27:395-398. |

| 35. Safer Opioid Supply Compared With Conventional Opioid Assisted Treatment (Methadone) "In this population-based study, individuals newly prescribed SOS typically had more comorbidities than people receiving methadone, with higher rates of alcohol use disorder, HIV, hepatitis C, opioid toxicity, infections, and recent engagement in OAT. After matching, we found reduced rates of clinical and health systems outcomes over time among individuals commencing SOS or methadone. In comparative analyses, people receiving SOS had higher rates of opioid toxicities, emergency department visits, inpatient hospitalisations, and incident infections compared with methadone recipients. Although these differences were attenuated after accounting for the high rates of treatment discontinuation during follow-up (which were higher among people who received methadone), rates of opioid toxicities remained higher among people commencing SOS compared with those commencing methadone. Taken together, this study highlights the potential complementary roles of prescribed SOS and methadone as options in response to the urgent drug toxicity crisis, particularly given the higher medical complexity and high rates of recent and concurrent OAT among people receiving SOS. "Our findings of reduced monthly rates of opioid-related toxicities, health-care use, hospital-treated infections, and non-primary-care-related health-care costs after initiation build upon earlier work showing improved clinical outcomes for people engaged with SOS programmes. Although we observed similar findings in a previous evaluation of a single large SOS programme in London (ON, Canada), that study was not powered to detect changing opioid toxicity rates over time.11 By contrast, we found lower rates of opioid toxicities over time among SOS recipients in this province-wide study. Furthermore, an evaluation of risk mitigation guidance (RMG) prescribing in British Columbia, Canada,15 found significant declines in overdose-related mortality in the week following receipt of an RMG opioid dispensation, with no significant effect on all-cause or overdose-related acute care visits. By contrast, we observed lower rates of acute health service use among people receiving SOS, probably reflecting the longer follow-up observation period in our study. Although our study was not powered to examine death as an outcome, these events were rare, with five or fewer opioid-related deaths among SOS recipients over a 1-year follow-up period. "A notable difference between our study and previous research is the comparison of outcomes between people commencing SOS and methadone. In between-group comparison, rates of opioid toxicities, all-cause emergency department visits, and hospitalisations were elevated among people newly prescribed SOS relative to individuals commencing methadone. Methadone is typically started at low doses because of the heightened risk of respiratory depression during the first month of therapy, with recent guidelines recommending rapid, safe titration to stable and effective doses for people who use fentanyl.20 Accordingly, short-duration outcomes with methadone reflect a complex mix of patients benefiting from treatment, having early toxicity, and having incompletely treated withdrawal and craving. For these reasons, focusing on 1-year outcomes among new recipients is important to capture the well established benefits of methadone for people retained in treatment.20 Our comparative results also reflect differences in drug-use patterns and the severity of opioid use disorder among SOS recipients that could not be accounted for using administrative health data, and differences in the goals of SOS and OAT programmes.19,21 For example, people receiving SOS had substantially higher rates of medical comorbidities at baseline than individuals commencing methadone, suggesting that SOS use was concentrated among individuals with high acuity and those with serious medical complications from drug use. Importantly, differences between people receiving SOS and those receiving methadone after propensity-score matching suggest that important between-group differences might persist, despite efforts to balance clinical and demographic characteristics and baseline patterns of substance use. Additionally, SOS is a harm reduction measure intended to reduce (but not necessarily eliminate) exposure to the unregulated drug supply for individuals who cannot or choose not to be engaged in OAT or who have tried OAT in the past without success.19,22,23 By contrast, there is variation in clinical approaches to methadone provision, with low-threshold methadone not strictly requiring abstinence from the unregulated drug supply,24 and methadone maintenance programmes typically incorporating more strict requirements for abstinence.25 Therefore, while both SOS and methadone recipients might sometimes access the unregulated drug supply, it is likely that this occurs at higher rates among SOS clients. As a result, we speculate that different patterns of unregulated drug use (eg, frequency of use, injection vs inhalation) and unmeasured differences in severity of opioid use disorder between groups could account, in part, for the higher event rates among SOS recipients." Gomes T, McCormack D, Kolla G, et al. Comparing the effects of prescribed safer opioid supply and methadone in Ontario, Canada: a population-based matched cohort study. Lancet Public Health. 2025;10(5):e412-e421. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(25)00070-2 |

| 36. Growth of Xylazine in US Drug Market "We summarize longitudinal, recent, and geographically specific evidence describing how xylazine is increasingly implicated in overdose deaths in jurisdictions spanning all major US regions and link it to detailed ethnographic observations of its use in Philadelphia open-air narcotics markets. Xylazine presence in overdose deaths grew exponentially during the observed period, rising nearly 20-fold between 2015 and 2020. Whereas the most recent national data from the State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System characterized the level of xylazine-present overdoses in 2019 (Kariisa, 2021), we found that the prevalence increased by nearly 50% from 2019 to 2020 alone, indicating a need for more recent data to guide the public health response. Furthermore, we find that even looking at only 10 jurisdictions a greater number of xylazine-present overdose deaths were seen in 2020 (854), than the previous study looking at 38 states in 2019 (826) (Kariisa, 2021), implying a very fast rate of growth nationally. "Xylazine prevalence was observed earliest and at the highest magnitude in the Northeast, and may be spreading west, in a pattern similar to the trajectory of illicitly-manufactured fentanyls in recent years (Shover et al., 2020). This similarity may not be incidental, as an analysis of the co-occurrence of fentanyl and xylazine indicates a strong ecological link, with fentanyl nearly universally implicated in xylazine-present overdose deaths. Further, ethnographic data among PWID suggests that the use of xylazine as an illicit drug additive may predominantly serve as a response to the short duration of fentanyl. By ‘giving fentanyl legs’—offering improved duration of effect—the addition of xylazine may confer a competitive market advantage for illicit opioid formulations that contain it, as it remedies one of the most commonly expressed complaints that PWID hold regarding fentanyl-based street opioid formulations." Friedman, J., Montero, F., Bourgois, P., Wahbi, R., Dye, D., Goodman-Meza, D., & Shover, C. (2022). Xylazine spreads across the US: A growing component of the increasingly synthetic and polysubstance overdose crisis. Drug and alcohol dependence, 233, 109380. doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2022.109380. |

| 37. The Criminal Legal System Response to Deaths from a Toxic Unregulated Drug Supply and Drug Overdose "The opioid overdose epidemic continues to evolve in the United States (US). While the epidemic began with prescription opioids in the 1990’s, it evolved to consist largely of heroin by 2010, and synthetic opioids by 2013, driven by high-potency illicitly manufactured fentanyl and fentanyl analogs (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2023). By 2019, half of the 70,630 drug overdose deaths in the US involved synthetic opioids; from 2013 to 2019, the age-adjusted synthetic opioid-involved death rate increased 1,040% from 1.0 to 11.4 per 100,000 (Mattson et al., 2021). From 2018 to 2019 alone, Colorado, the setting for this study, experienced the largest relative increase in the age-adjusted synthetic opioid-involved death rate of any state (95.5%). Further, in 2022, Colorado’s drug overdose death rate was 29.8 per 100,000, and has continued to climb annually, with fentanyl-involved deaths increasing 18.4% in 2023 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention., n.d.). "Criminal penalties have long been a tool used to combat the overdose epidemic with more individuals being arrested for drug offenses than any other offense type in 2019, accounting for 1 in 10 of all arrests (Horowitz et al., 2022). However, increased criminal legal penalties - such as assigning felonies as opposed to misdemeanors for drug possession - are not associated with reductions in drug use or recidivism, but with worsened health and well-being, reduced job and housing opportunities, and increased risk of non-fatal and fatal overdose post-release from incarceration (Gelb et al., 2018; Wildeman & Wang, 2017). Further, these penalties, and their effects on health, employment, and housing, are applied in a racially disparate way. While Black individuals made up 12% of the US adult population in 2019, they accounted for 27% of drug-related arrests (Horowitz et al., 2022). "In the midst of the growing and evolving overdose epidemic, many states have introduced legislation to increase criminal penalties for drug possession, particularly fentanyl possession (Hill, 2023). In May of 2022, Colorado passed House Bill (HB) 22-1326, The Fentanyl Accountability and Prevention Bill. The bill was signed into law in July 2022, with key components taking effect at that time. One such component was that the bill increased penalties for possessing drugs weighing 1–4 g that knowingly contain fentanyl from a misdemeanor to a felony (Fentanyl Accountability And Prevention, 2022). Misdemeanors in Colorado may not include an incarceration sentence but can include a sentence in jail (a county-run facility where individuals are often held pre-trial or when sentenced for less than one year) whereas felonies are more serious and are more likely to result in a prison sentence (a state-run facility where individuals are often incarcerated when they receive a sentence to one or more years) (McCann, 2024)." LeMasters, K., Nall, S., Jurecka, C. et al. “You can’t incarcerate yourself out of the drug problem in America:” A qualitative examination of Colorado’s 2022 Fentanyl criminalization law. Health Justice 13, 26 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40352-025-00334-8 |

| 38. Impact of Increased Criminal Penalties on Health and Community "This work adds to a growing body of literature on how increased criminal penalties for drug possession and distribution affect health. Prior work has documented that the criminal legal system can be a stigmatizing revolving door that people often struggle to escape (Jones & Sawyer, 2019; LeMasters et al., 2023a). Our work expands on this notion by highlighting how increased penalties specifically for fentanyl possession contribute to this revolving door, as people often use drugs to cope with the stress and stigmatization of criminal legal involvement, which only continues their involvement in this system. Our work also highlights that while views were largely the same in urban and rural areas, relationships between law enforcement and PWUD in rural areas may be more positive due to long-standing individual relationships and the lack of other community services that require engagement with law enforcement. This echoes prior work that has found some rural law enforcement to be supportive of syringe exchange programs, but is counter to prior work that found rural law enforcement’s views towards PWUD to be particularly stigmatizing (Allen et al., 2022; Ezell et al., 2021). "Results from this study also highlight a tension between increasing jail and police funding to better address SUD and shifting this funding to community agencies that are not part of the criminal legal system. Work by the American Civil Liberties Union states that MOUD treatment programs in prisons and jails, while necessary, should never justify incarceration itself (American Civil Liberties Union, 2021). Yet, in many counties in Colorado, jails are the only place where MOUD is provided, emphasizing the need to invest in long-term community solutions. For instance, as outlined by a national coalition of recovery and harm reduction organizations, government agencies should allocate opioid abatement funds to proven public health solutions (e.g., overdose prevention centers), housing and wraparound support services (e.g., supportive housing programs), addressing collateral consequences of Drug War policies (e.g., second-chance employment programs), and supporting community-based organizations rather than further criminalizing substance use (A Roadmap for Opioid Settlement Funds: Supporting Communities & Ending the Overdose Crisis, n.d.). Results from our work highlight that within pre-existing community-based organizations, there is a need to both increase messaging from those providing services to PWUD to ensure that individuals are aware of their rights under the Good Samaritan Laws and to ensure that policing efforts are also aligned with the Good Samaritan Law (Koester et al., 2017; Schneider et al., 2020)." LeMasters, K., Nall, S., Jurecka, C. et al. “You can’t incarcerate yourself out of the drug problem in America:” A qualitative examination of Colorado’s 2022 Fentanyl criminalization law. Health Justice 13, 26 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40352-025-00334-8 |

| 39. Xylazine in Puerto Rico "Prior to the widespread availability of xylazine in the Philadelphia drug supply, it was often mentioned in passing by residents of the majority Puerto Rican neighborhood where our fieldwork was based as a powerfully psychoactive additive ‘“back on the Island”.’ Xylazine was occasionally detected in fatal overdoses in Philadelphia as early as 2006 (Wong et al., 2008), but it was not common knowledge among PWID. Significantly, however, many of our long-term informants recently immigrating/returning from Puerto Rico spoke with a mix of intrigue and apprehension about the psychoactive effects and health risks of 'anastesia de caballo [horse tranquilizer]'." Friedman, J., Montero, F., Bourgois, P., Wahbi, R., Dye, D., Goodman-Meza, D., & Shover, C. (2022). Xylazine spreads across the US: A growing component of the increasingly synthetic and polysubstance overdose crisis. Drug and alcohol dependence, 233, 109380. doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2022.109380. |

| 40. Introduction of Xylazine to Philadelphia "At least a decade after Xylazine became a fixture in Puerto Rico, it entered the street opioid supply in Philadelphia as a more prevalent additive in the mid-2010s. The shift was noted by PWID, as well as harm reductionists and city public health officials (Johnson et al., 2021). PWID began to describe xylazine – often referred to as tranq – as a known element of specific ‘stamps’ or brands of opioid products in the illicit retail market. Opioid formulations containing xylazine, (e.g.,'tranq dope') became largely sought-after, as the addition of xylazine was reported to improve the euphoria and prolong the duration of fentanyl injections, in particular, solving 'the problem' of the 'short legs' of the otherwise euphoric effects of illicitly manufactured fentanyl." Friedman, J., Montero, F., Bourgois, P., Wahbi, R., Dye, D., Goodman-Meza, D., & Shover, C. (2022). Xylazine spreads across the US: A growing component of the increasingly synthetic and polysubstance overdose crisis. Drug and alcohol dependence, 233, 109380. doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2022.109380. |

| 41. Good Samaritan and Naloxone Access Laws Save Lives "GAO found that 48 jurisdictions (47 states and D.C.) have enacted both Good Samaritan and Naloxone Access laws. Kansas, Texas and Wyoming do not have a Good Samaritan law for drug overdoses but have a Naloxone Access law. The five U.S. territories do not have either type of law. GAO also found that the laws vary. For example, Good Samaritan laws vary in the types of drug offenses that are exempt from prosecution and whether this immunity takes effect before an individual is arrested or charged, or after these events but before trial. "GAO reviewed 17 studies that provide potential insights into the effectiveness of Good Samaritan laws in reducing overdose deaths or the factors that may contribute to a law’s effectiveness. GAO found that, despite some limitations, the findings collectively suggest a pattern of lower rates of opioid-related overdose deaths among states that have enacted Good Samaritan laws, both compared to death rates prior to a law’s enactment and death rates in states without such laws. In addition, studies found an increased likelihood of individuals calling 911 if they are aware of the laws. However, findings also suggest that awareness of Good Samaritan laws may vary substantially across jurisdictions among both law enforcement officers and the public, which could affect their willingness to call 911." "Most States Have Good Samaritan Laws and Research Indicates They May Have Positive Effects," US General Accountability Office, March 2021, GAO-21-248. |