Overdose and Overdose Mortality

The US Centers for Disease Control reports, using provisional data available for analysis on July 6, 2025, that in calendar year 2024 at least 80,719 people in the US are reported to have died from drug overdose and toxins in the unregulated drug supply. These provisional data are incomplete and the CDC predicts that the final number of deaths in the US due to overdose and toxins in the unregulated drug supply in calendar year 2024 will be 81,740.

- In the 12-month period ending January 31, 2025, at least 78,594 people in the US were reported to have died from drug overdose and toxins in the unregulated drug supply. The CDC predicts that the final number of overdose deaths in that period will be 79,929.

- In calendar year 2023, at least 106,881 people in the US were reported to have died from drug overdose and toxins in the unregulated drug supply. The CDC predicts that the final number of overdose deaths in calendar year 2023 will be 108,550.

- In calendar year 2022, at least 109,413 people in the US were reported to have died from drug overdose and toxins in the unregulated drug supply. The CDC predicts that the final number of overdose deaths in calendar year 2022 will be 110,942.

- In calendar year 2021, at least 107,573 people in the US were reported to have died from drug overdose and toxins in the unregulated drug supply. The CDC predicts that the final number of overdose deaths in calendar year 2021 will be 109,099.

Source: Ahmad FB, Cisewski JA, Rossen LM, Sutton P. Provisional drug overdose death counts. Centers for Disease Control, National Center for Health Statistics. 2025. Last accessed July 24, 2025.

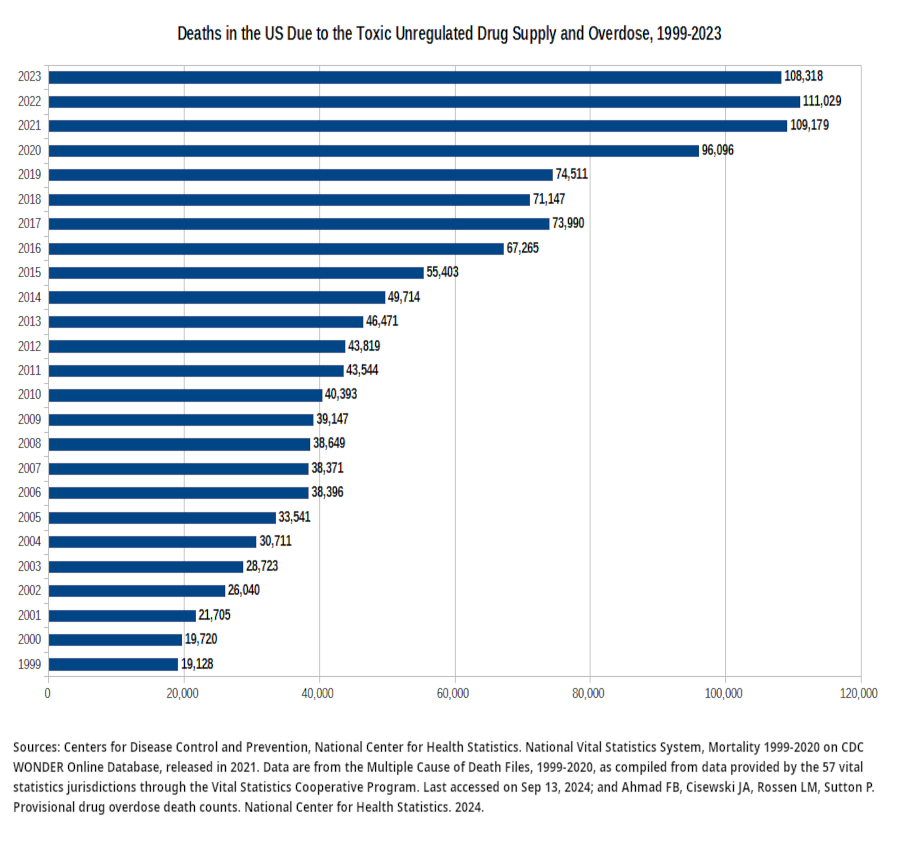

1. Deaths in the US Due to the Toxic Unregulated Drug Supply and Overdose, 1999-2023 |

| 2. Deaths in the US in 2022 Due to a Toxic Unregulated Drug Supply and Overdose "● In 2022, 107,941 drug overdose deaths occurred, resulting in an age-adjusted rate of 32.6 deaths per 100,000 standard population (Figure 1). "● Overall, the age-adjusted rate of drug overdose deaths nearly quadrupled from 8.2 in 2002 to 32.6 in 2022; however, the rate did not significantly change between 2021 (32.4) and 2022 (32.6). "● Between 2021 and 2022, the age-adjusted rate of drug overdose deaths for males increased 1.1% from 45.1 to 45.6, while the rate for females decreased 1.0% from 19.6 to 19.4, although this decrease was not significant. Spencer MR, Garnett MF, Miniño AM. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 2002–2022. NCHS Data Brief, no 491. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2024. DOI: dx.doi.org/10.15620/cdc:135849 |

| 3. Overdose Education and Naloxone Distribution (OEND) Within Syringe Service Programs (SSPs) "Among the 342 known SSPs operating at the beginning of 2019, 263 (77%) responded to the online survey; of these, 247 (94%) had an OEND program, 160 (65%) of which had been implemented since 2016 (Figure 1). With regard to phases of OEND implementation, 173 (66%) responding SSPs had been implementing OEND for 12 months or more, 74 (28%) had implemented OEND within the last 12 months, eight (3%) were actively preparing for OEND implementation, and eight (3%) were exploring OEND implementation (Table). Of the 16 SSPs not yet offering OEND, four had previously implemented naloxone distribution but stopped because of an inadequate naloxone supply or funding. "Among the 247 SSPs with an OEND program, 191 (77%) offered OEND every time syringe services were offered, and 214 (87%) provided naloxone refills as often as participants requested them (Table). SSPs reported offering OEND for a median of 15 of the past 28 days. Only 29 (12%) SSPs entered OEND data directly into an electronic data system. During the preceding 12 months, 237 (96%) of 247 SSPs with OEND programs reported distributing 702,232 naloxone doses, including refills, to 230,506 persons (an average of 3 doses per person). Sixty-two (26%) SSPs reported distributing naloxone to >1,000 persons in the last 12 months; these programs had distributed naloxone to 186,603 laypersons, who represented 81% of all recipients in the past 12 months. Overall, 14 (6%) SSPs reported distribution of ≥10,000 naloxone doses during the last 12 months, accounting for 382,132 naloxone doses, 54% of all doses distributed by SSPs in the past 12 months. These 14 SSPs are located throughout six of the nine census divisions. Seventy-two (29%) SSPs ran out of naloxone or needed to ration their naloxone in the preceding 3 months." Lambdin, B. H., Bluthenthal, R. N., Wenger, L. D., Wheeler, E., Garner, B., Lakosky, P., & Kral, A. H. (2020). Overdose Education and Naloxone Distribution Within Syringe Service Programs - United States, 2019. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 69(33), 1117–1121. doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6933a2 |

| 4. Emergency Department Visits and Trends Related to Cocaine, Psychostimulants, and Opioids in the United States, 2008–2018 "Psychostimulant-related ED visits increased from 2.2 to 12.9 visits per 10,000 population from 2008 to 2018. This is consistent with studies showing increasing national rates of ED visits, hospitalizations, and deaths from psychostimulant overdose [2, 4, 5, 33]. The increasing use of the ED and other acute care settings is likely linked to rising methamphetamine availability and use [34]. National Forensic Laboratory Information System data found methamphetamine case submissions increased from 2011 to 2019, with methamphetamine as the most frequently reported drug [35]. While psychostimulant-related ED visits were predominantly among Western regions in our study, recent data highlights the emergence of psychostimulant-related overdose deaths in the Midwest and Northeast, suggesting methamphetamine is already a nationwide concern [8, 36]. Increases in cocaine-related ED visits were not significant, potentially due to the exclusion of visits related to opioid and cocaine co-use. Polysubstance use is common in among individuals using cocaine [30], and other studies found rates of fatal overdoses and ED visits for overdose involving cocaine and opioid use are rising [5, 33]. "We found stimulant-related ED visits were less likely to be identified as drug toxicity/withdrawal concerns, underscoring the differences in presentations between stimulant- and opioid-related visits. While the national surge in ED visits and deaths related to opioid overdose is linked to the rise in fentanyl in the drug supply [1, 33, 37], the main drivers of stimulant-related ED visits and overdoses are unclear. Possibilities include increased potency of fluctuating drug supplies [35], contamination or co-use with synthetic opioids like fentanyl [38], or the cumulative effects of chronic stimulant use over time [39]. Further, the term “overdose”, when applied to opioids commonly refers to an acute respiratory event from an episode of use, and this term is problematic when applied to stimulants, as it lacks specificity in capturing the diverse ways in which stimulant toxicity can present [16, 40]. Our data suggest that acute emergency presentations related to stimulant use are more likely due to the cumulative effect of stimulant use over time rather than from a single episode of use. Addressing acute stimulant toxicity may rely more on clinical management of various symptoms, rather than the development of a single reversal agent like naloxone for opioid overdose." Suen, L.W., Davy-Mendez, T., LeSaint, K.T. et al. Emergency department visits and trends related to cocaine, psychostimulants, and opioids in the United States, 2008–2018. BMC Emerg Med 22, 19 (2022). doi.org/10.1186/s12873-022-00573-0. |

| 5. Drug Overdose Rates In The US, 2019 "The age-adjusted rate for drug overdose deaths in the United States for 2019 was 21.6 per 100,000 standard population (Figure 1, Table). The five states with the highest rates were West Virginia (52.8), Delaware (48.0), District of Columbia (43.2), Ohio (38.3), and Maryland (38.2). The five states with the lowest rates were Nebraska (8.7), South Dakota (10.5), Texas (10.8), North Dakota (11.4), and Iowa (11.5). "The age-adjusted drug overdose death rate for the non-Hispanic white population in 2019 (26.2 per 100,000 standard population) was 21.3% higher than the national rate (Figure 2). The rate for the non-Hispanic black population (24.8) was 14.8% higher than the national rate. The rate for the non-Hispanic American Indian or Alaska Native population (30.5) was 41.2% higher than the national rate. The rate for the non-Hispanic Asian population (3.3) was 84.7% lower than the national rate. The rate for the non-Hispanic Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander population (9.5) was 56.0% lower than the national rate. The rate for the Hispanic population (12.7) was 41.2% lower than the national rate." Miniño AM, Hedegaard H. Drug poisoning mortality, by state and by race and ethnicity: United States, 2019. NCHS Health E-Stats. 2021. |

| 6. Deaths Attributed To Drug Overdose In The US In 2018 "● In 2018, there were 67,367 drug overdose deaths in the United States, a 4.1% decline from 2017 (70,237 deaths). "● The age-adjusted rate of drug overdose deaths in 2018 (20.7 per 100,000) was 4.6% lower than in 2017 (21.7). "● For 14 states and the District of Columbia, the drug overdose death rate was lower in 2018 than in 2017. "● The rate of drug overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids other than methadone (drugs such as fentanyl, fentanyl analogs, and tramadol) increased by 10%, from 9.0 in 2017 to 9.9 in 2018. "● From 2012 through 2018, the rate of drug overdose deaths involving cocaine more than tripled (from 1.4 to 4.5) and the rate for deaths involving psychostimulants with abuse potential (drugs such as methamphetamine) increased nearly 5-fold (from 0.8 to 3.9)." Hedegaard H, Miniño AM, Warner M. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999–2018. NCHS Data Brief, no 356. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2020. |

| 7. Unprecedented Increases In Overdose Mortality In First Seven Months Of 2020 "By disaggregating monthly trends, we found that unprecedented increases in overdose mortality occurred during the early months of pandemic in the United States. At the peak, overdose deaths in May 2020 were elevated by nearly 60% compared with the previous year, and the first 7 months of 2020 were overall elevated by 35% compared with the same period for 2019. To put this in perspective, if the final values through December 2020 were to be elevated by a similar margin, we would expect a total of 93,000 to 98,000 deaths to eventually be recorded for the year. Values for the remaining 5 months of 2020 have yet to be seen; however, it is very likely that 2020 will represent the largest year-to-year increase in overdose mortality in recent history for the United States." Joseph Friedman , Samir Akre , “COVID-19 and the Drug Overdose Crisis: Uncovering the Deadliest Months in the United States, January‒July 2020”, American Journal of Public Health 111, no. 7 (July 1, 2021): pp. 1284-1291. |

| 8. Deaths in 2017 in the US Attributed to Drug Overdose " In 2017, there were 70,237 drug overdose deaths in the United States. " The age-adjusted rate of drug overdose deaths in 2017 (21.7 per 100,000) was 9.6% higher than the rate in 2016 (19.8). " Adults aged 25–34, 35–44, and 45–54 had higher rates of drug overdose deaths in 2017 than those aged 15–24, 55–64, and 65 and over. " West Virginia (57.8 per 100,000), Ohio (46.3), Pennsylvania (44.3), and the District of Columbia (44.0) had the highest age-adjusted drug overdose death rates in 2017. " The age-adjusted rate of drug overdose deaths involving synthetic opioids other than methadone (drugs such as fentanyl, fentanyl analogs, and tramadol) increased by 45% between 2016 and 2017, from 6.2 to 9.0 per 100,000." Hedegaard H, Miniño AM, Warner M. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999–2017. NCHS Data Brief, no 329. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2018. |

| 9. Changes in Synthetic Opioid Involvement in Overdose Deaths in the US and Involvement of Other Drugs in Combination "Among the 42,249 opioid-related overdose deaths in 2016, 19,413 involved synthetic opioids, 17,087 involved prescription opioids, and 15,469 involved heroin. Synthetic opioid involvement in these deaths increased significantly from 3007 (14.3% of opioid-related deaths) in 2010 to 19,413 (45.9%) in 2016 (P for trend <.01). Significant increases in synthetic opioid involvement in overdose deaths involving prescription opioids, heroin, and all other illicit or psychotherapeutic drugs were found from 2010 through 2016 (Table). "Among synthetic opioid–related overdose deaths in 2016, 79.7% involved another drug or alcohol. The most common co-involved substances were another opioid (47.9%), heroin (29.8%), cocaine (21.6%), prescription opioids (20.9%), benzodiazepines (17.0%), alcohol (11.1%), psychostimulants (5.4%), and antidepressants (5.2%) (Figure)." Jones CM, Einstein EB, Compton WM. Changes in Synthetic Opioid Involvement in Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States, 2010-2016. JAMA. 2018;319(17):1819–1821. |

| 10. Deaths in the US in 2022 Involving Cocaine or Stimulants "● The age-adjusted rate of drug overdose deaths involving cocaine increased slightly from 1.6 deaths per 100,000 standard population in 2002 to 2.5 in 2006, decreased to 1.3 in 2010, then increased to 8.2 in 2022; the rate in 2022 was 12.3% higher than the rate in 2021 (7.3) (Figure 5). "● The age-adjusted rate of drug overdose deaths involving psychostimulants with abuse potential (subsequently, psychostimulants), which includes methamphetamine, amphetamine, and methylphenidate, was 4.0% higher in 2022 than the rate in 2021 (10.4 compared with 10.0). "● The age-adjusted rate of drug overdose deaths involving psychostimulants increased more than 34 times from 2002 (0.3) to 2022 (10.4), with different rates of change over time." Spencer MR, Garnett MF, Miniño AM. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 2002–2022. NCHS Data Brief, no 491. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2024. DOI: dx.doi.org/10.15620/cdc:135849 |

| 11. Decriminalization and Deaths from a Toxic Unregulated Drug Supply and Overdose "Oregon and Washington have recently made changes to their drug laws to fully or partially legalize possession of small amounts of drugs and increase investment in treatment access. To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate the association between those changes and fatal drug overdose. Using the synthetic control method to compare post-drug policy changes in fatal drug overdose rates in Oregon and Washington and estimated rates in the absence of these drug policy changes, we found no evidence that either Measure 110 in Oregon or the Washington Blake decision and subsequent legislative amendments were associated with changes in fatal drug overdose rates in either state. These findings were also robust to variations in the donor pool and the modeling strategy." Joshi S, Rivera BD, Cerdá M, et al. One-Year Association of Drug Possession Law Change With Fatal Drug Overdose in Oregon and Washington. JAMA Psychiatry. Published online September 27, 2023. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.3416 |

| 12. Drug Poisoning Deaths In The US, 2019 "In 2019, 70,630 deaths from the toxic effects of drug poisoning (drug overdose) occurred in the United States (1), a 4.8% increase compared with 2018 and the highest recorded number in recent history." Miniño AM, Hedegaard H. Drug poisoning mortality, by state and by race and ethnicity: United States, 2019. NCHS Health E-Stats. Centers for Disease Control, National Center for Health Statistics, 2021. |

| 13. Naloxone "Naloxone has been used as an antidote to opioids for over 50 years, and the drug has been readily available as a parenteral formula. Naloxone acts as a pure μ-opioid receptor competitive antagonist and is instrumental in preventing accidental overdose of opioids. Due to its effectiveness in preventing death due to opioid overdose, the federal government has recommended that naloxone should be available over-the-counter at most pharmacies. Naloxone can be obtained without a prescription in 43 states and can be administered by emergency medical personnel and law enforcement officials. With the availability of naloxone over the counter, it is now easier for family members and caregivers of patients with opioid use disorder to administer naloxone and potentially save lives.[1]" Jordan MR, Patel P, Morrisonponce D. Naloxone. [Updated 2024 May 5]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024. |

| 14. Routes of Administration and Deaths from Toxic Drug Supply and Drug Overdose "From January–June 2020 to July–December 2022, the number of overdose deaths with evidence of smoking doubled, and the percentage of deaths with evidence of smoking increased across all geographic regions. By late 2022, smoking was the predominant route of use among drug overdose deaths overall and in the Midwest and West regions. Increases were most pronounced when IMFs were detected, with or without stimulants. Increases in the number and percentage of deaths with evidence of smoking, and the corresponding decrease in those with evidence of injection, might be partially driven by 1) the transition from injecting heroin to smoking IMFs [Illicitly Manufactured Fentanyl] (3,4), 2) increases in deaths co-involving IMFs and stimulants that might be smoked†††† (1), and 3) increases in the use of counterfeit pills, which frequently contain IMFs and are often smoked (7). Motivations for transitioning from injection to smoking include fewer adverse health effects (e.g., fewer abscesses), reduced cost and stigma, sense of more control over drug quantity consumed per use (e.g., smoking small amounts during a period versus a single injection bolus), and a perception of reduced overdose risk among persons who use drugs (3,5,8). These motivations might also signify lower barriers for initiating drug use by smoking, or for transitioning from ingestion to smoking; compared with ingestion, smoking can intensify drug effects and increase overdose risk (9). Despite some risk reduction associated with smoking compared with injection (e.g., fewer bloodborne infections), smoking carries substantial overdose risk because of rapid drug absorption (5,9). "Nearly 80% of overdose deaths with evidence of smoking had no evidence of injection; persons who use drugs by smoking but do not inject drugs might not use traditional syringe services programs where harm reduction messaging and supplies are often provided. In response, some jurisdictions have adapted harm reduction services to provide safer smoking supplies or established health hubs to expand reach to persons using drugs through noninjection routes.§§§§ In addition, harm reduction services (e.g., peer outreach and provision of fentanyl test strips for testing drug products and naloxone to reverse opioid overdoses), messaging specific to smoking drugs, and linkage to treatment for substance use disorders can be integrated into other health care delivery (e.g., emergency departments) and public safety (e.g., drug diversion) settings. "The percentage and number of deaths with evidence of injection decreased across regions and drug categories. Observed decreases might reflect transitions to noninjection routes and response to public health efforts to reduce injection drug use because of its risk for overdose and infectious disease transmission (3,4,10). Despite these declines, more than 4,000 drug overdose deaths had evidence of injection during July–December 2022. Syringe services programs help to engage persons who use drugs in services (10); sustained efforts to provide sterile injection supplies, additional harm reduction tools, and linkage to treatment for substance use disorders, including medications for opioid use disorder, are important for further reduction in the number of overdose deaths from injection drug use. Lessons learned from implementing syringe services programs could be applied to other harm reduction and outreach models to reach more persons who use drugs by any route." Tanz LJ, Gladden RM, Dinwiddie AT, et al. Routes of Drug Use Among Drug Overdose Deaths — United States, 2020–2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2024;73:124–130. DOI: dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7306a2 |

| 15. Co-Involvement of Stimulants and Fentanyl in Drug-Related Deaths in the US, 2010-2021 "Findings "The percent of US overdose deaths involving both fentanyl and stimulants increased from 0.6% (n = 235) in 2010 to 32.3% (34 429) in 2021, with the sharpest rise starting in 2015. In 2010, fentanyl was most commonly found alongside prescription opioids, benzodiazepines, and alcohol. In the Northeast this shifted to heroin-fentanyl co-involvement in the mid-2010s, and nearly universally to cocaine-fentanyl co-involvement by 2021. Universally in the West, and in the majority of states in the South and Midwest, methamphetamine-fentanyl co-involvement predominated by 2021. The proportion of stimulant involvement in fentanyl-involved overdose deaths rose in virtually every state 2015–2021. Intersectional group analysis reveals particularly high rates for older Black and African American individuals living in the West. "Conclusions "By 2021 stimulants were the most common drug class found in fentanyl-involved overdoses in every state in the US. The rise of deaths involving cocaine and methamphetamine must be understood in the context of a drug market dominated by illicit fentanyls, which have made polysubstance use more sought-after and commonplace. The widespread concurrent use of fentanyl and stimulants, as well as other polysubstance formulations, presents novel health risks and public health challenges." Friedman, J, Shover, CL. Charting the fourth wave: Geographic, temporal, race/ethnicity and demographic trends in polysubstance fentanyl overdose deaths in the United States, 2010–2021. Addiction. 2023. doi.org/10.1111/add.16318 |

| 16. Key Factors Underlying Increasing Rates of Heroin Use and Opioid Overdose in the US "A key factor underlying the recent increases in rates of heroin use and overdose may be the low cost and high purity of heroin.45,46 The price in retail purchases has been lower than $600 per pure gram every year since 2001, with costs of $465 in 2012 and $552 in 2002, as compared with $1237 in 1992 and $2690 in 1982.45 A recent study showed that each $100 decrease in the price per pure gram of heroin resulted in a 2.9% increase in the number of hospitalizations for heroin overdose.46" Wilson M. Compton, M.D., M.P.E., Christopher M. Jones, Pharm.D., M.P.H., and Grant T. Baldwin, Ph.D., M.P.H. Relationship between Nonmedical Prescription-Opioid Use and Heroin Use. N Engl J Med 2016; 374:154-163. January 14, 2016. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMra1508490. |

| 17. Drug Overdose Deaths In 2018 - Demographic Details and Changes from 2017 "During 2018, drug overdoses resulted in 67,367 deaths in the United States, a 4.1% decrease from 2017. Among these drug overdose deaths, 46,802 (69.5%) involved an opioid. From 2017 to 2018, opioid-involved death rates decreased 2.0%, from 14.9 per 100,000 population to 14.6 (Table 1); decreases occurred among females; persons aged 15–34 years and 45–54 years; non-Hispanic whites; and in small metro, micropolitan, and noncore areas; and in the Midwest and South regions. Rates during 2017–2018 increased among persons aged ≥65 years, non-Hispanic blacks, and Hispanics, and in the Northeast and the West regions. Rates decreased in 11 states and DC and increased in three states, with the largest relative (percentage) decrease in Iowa (–30.4%) and the largest absolute decrease (difference in rates) in Ohio (–9.6); the largest relative and absolute increase occurred in Missouri (18.8%, 3.1). The highest opioid-involved death rate in 2018 was in West Virginia (42.4 per 100,000). "Prescription opioid-involved death rates decreased by 13.5% from 2017 to 2018. Rates decreased in males and females, persons aged 15–64 years, non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics, non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Natives, and across all urbanization levels. Prescription opioid–involved death rates remained stable in the Northeast and decreased in the Midwest, South, and the West. Seventeen states experienced declines in prescription opioid–involved death rates, with no states experiencing significant increases. The largest relative decrease occurred in Ohio (–40.5%), whereas the largest absolute decrease occurred in West Virginia (–4.1), which also had the highest prescription opioid-involved death rate in 2018 (13.1 per 100,000). "Heroin-involved death rates decreased 4.1% from 2017 to 2018; reductions occurred among males and females, persons aged 15–34 years, non-Hispanic whites, and in large central metro and large fringe metro areas (Table 2). Rates decreased in the Midwest and increased in the West. Rates decreased in seven states and DC and increased in three states from 2017 to 2018. The largest relative decrease occurred in Kentucky (50.0%), and the largest absolute decrease occurred in DC (–7.1); the largest relative and absolute increase was in Tennessee (18.8%, 0.9). The highest heroin-involved death rate in 2018 was in Vermont (12.5 per 100,000). "Death rates involving synthetic opioids increased from 9.0 per 100,000 population in 2017 to 9.9 in 2018 and accounted for 67.0% of opioid-involved deaths in 2018. These rates increased from 2017 to 2018 among males and females, persons aged ≥25 years, non-Hispanic whites, non-Hispanic blacks, Hispanics, non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islanders, and in large central metro, large fringe metro, medium metro, and small metro counties. Synthetic opioid–involved death rates increased in the Northeast, South and West and remained stable in the Midwest. Rates increased in 10 states and decreased in two states. The largest relative increase occurred in Arizona (92.5%), and the largest absolute increase occurred in Maryland and Missouri (4.4 per 100,000 in both states); the largest relative and absolute decrease was in Ohio (–20.7%, –6.7). The highest synthetic opioid–involved death rate in 2018 occurred in West Virginia (34.0 per 100,000)." Wilson N, Kariisa M, Seth P, Smith H IV, Davis NL. Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths — United States, 2017–2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:290–297. |

| 18. Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths in the US 2017-2018 "Of the 70,237 drug overdose deaths in the United States in 2017, approximately two thirds (47,600) involved an opioid (1). In recent years, increases in opioid-involved overdose deaths have been driven primarily by deaths involving synthetic opioids other than methadone (hereafter referred to as synthetic opioids) (1). CDC analyzed changes in age-adjusted death rates from 2017 to 2018 involving all opioids and opioid subcategories* by demographic characteristics, county urbanization levels, U.S. Census region, and state. During 2018, a total of 67,367 drug overdose deaths occurred in the United States, a 4.1% decline from 2017; 46,802 (69.5%) involved an opioid (2). From 2017 to 2018, deaths involving all opioids, prescription opioids, and heroin decreased 2%, 13.5%, and 4.1%, respectively. However, deaths involving synthetic opioids increased 10%, likely driven by illicitly manufactured fentanyl (IMF), including fentanyl analogs (1,3)." Wilson N, Kariisa M, Seth P, Smith H 4th, Davis NL. Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths - United States, 2017-2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(11):290‐297. Centers for Disease Control. Published 2020 Mar 20. |

| 19. Association of Dose Tapering With Overdose or Mental Health Crisis Among Patients Prescribed Long-term Opioids "In a large cohort of patients in the US prescribed stable, longterm, higher-dose opioids, undergoing opioid dose tapering was associated with statistically significant risk of subsequent overdose and mental health crisis, including suicidality." Agnoli A, Xing G, Tancredi DJ, Magnan E, Jerant A, Fenton JJ. Association of Dose Tapering With Overdose or Mental Health Crisis Among Patients Prescribed Long-term Opioids. JAMA. 2021;326(5):411–419. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.11013 |

| 20. Drugs Most Frequently Involved in Drug Overdose Deaths in the US 2011–2016 "The percentage of deaths with concomitant involvement of other drugs varied by drug. For example, almost all drug overdose deaths involving alprazolam or diazepam (96%) mentioned involvement of other drugs. In contrast, 50% of the drug overdose deaths involving methamphetamine, and 69% of the drug overdose deaths involving fentanyl mentioned involvement of one or more other specific drugs. "Table D shows the most frequent concomitant drug mentions for each of the top 10 drugs involved in drug overdose deaths in 2016. " Two in five overdose deaths involving cocaine also mentioned fentanyl. " Nearly one-third of drug overdose deaths involving fentanyl also mentioned heroin (32%). " Alprazolam was mentioned in 26% of the overdose deaths involving hydrocodone, 22% of the deaths involving methadone, and 25% of the deaths involving oxycodone. " More than one-third of the overdose deaths involving cocaine also mentioned heroin (34%). " More than 20% of the overdose deaths involving methamphetamine also mentioned heroin." Hedegaard H, Bastian BA, Trinidad JP, Spencer M, Warner M. Drugs most frequently involved in drug overdose deaths: United States, 2011–2016. National Vital Statistics Reports; vol 67 no 9. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2018. |

| 21. Drugs Most Frequently Mentioned in Overdose Deaths in the US 2011-2016 "The number of drug overdose deaths per year increased 54%, from 41,340 deaths in 2011 to 63,632 deaths in 2016 (Table A). From the literal text analysis, the percentage of drug overdose deaths mentioning at least one specific drug or substance increased from 73% of the deaths in 2011 to 85% of the deaths in 2016. The percentage of drug overdose deaths that mentioned only a drug class but not a specific drug or substance declined from 5.1% of deaths in 2011 to 2.5% in 2016. Review of the literal text for these deaths indicated that the deaths that mentioned only a drug class frequently involved either an opioid or an opiate (ranging from 54% in 2015 to 60% in 2016). The percentage of deaths that did not mention a specific drug or substance or a drug class declined from 22% of drug overdose deaths in 2011 to 13% in 2016." Hedegaard H, Bastian BA, Trinidad JP, Spencer M, Warner M. Drugs most frequently involved in drug overdose deaths: United States, 2011–2016. National Vital Statistics Reports; vol 67 no 9. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2018. |

| 22. Drugs Most Frequently Involved in Drug Overdose Deaths in the US 2011–2016 "For the top 15 drugs: " Among drug overdose deaths that mentioned at least one specific drug, oxycodone ranked first in 2011,heroin from 2012 through 2015, and fentanyl in 2016. " In 2011 and 2012, fentanyl was mentioned in approximately 1,600 drug overdose deaths each year, but mentions increased in 2013 (1,919 deaths),2014 (4,223 deaths), 2015 (8,251 deaths), and 2016(18,335 deaths). In 2016, 29% of all drug overdose deaths mentioned involvement of fentanyl. " The number of drug overdose deaths involving heroin increased threefold, from 4,571 deaths or 11% of all drug overdose deaths in 2011 to 15,961 deaths or 25% of all drug overdose deaths in 2016. " Throughout the study period, cocaine ranked second or third among the top 15 drugs. From 2014 through 2016, the number of drug overdose deaths involving cocaine nearly doubled from 5,892 to 11,316. " The number of drug overdose deaths involving methamphetamine increased 3.6-fold, from 1,887 deaths in 2011 to 6,762 deaths in 2016. " The number of drug overdose deaths involving methadone decreased from 4,545 deaths in 2011 to 3,493 deaths in 2016." Hedegaard H, Bastian BA, Trinidad JP, Spencer M, Warner M. Drugs most frequently involved in drug overdose deaths: United States, 2011–2016. National Vital Statistics Reports; vol 67 no 9. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2018. |

| 23. Rescue Breathing and Naloxone in Response to Overdose "Relevant literature on overdose response included 3 clinical guidelines,1,21,32 3 grey literature reports (a rapid review,36 an evidence brief37 and a report of a technical working group on resuscitation training38), and a pilot and feasibility study.39 The conclusions in these resources differ on overdose response, notably on the role of rescue breathing and the order in which resuscitation steps occur. An in-depth discussion of the literature is available in Appendix 1, and Appendix 3 contains more detail on findings and included studies. "As the mandate of THN [Take Home Naloxone] programs includes overdose response training, our recommendation focuses on trained overdose response. Evidence from the Naloxone Guidance Development Group indicates that community overdose responders are effectively trained through different methods. For the purposes of this document, we recognize that people using THN programs may be trained on overdose response through their peers, using online resources, THN programs or cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) training courses. "In the literature, multiple sources identified naloxone administration and calling 911 or other emergency response numbers as critical steps in overdose response.1,21,32,36,38,39 Three guidance documents included verbal and physical stimulation to assess whether someone is experiencing overdose and to stimulate breathing.21,32,38 "For a responder trained in overdose response, guidance may differ according to whether the responder suspects respiratory depression or cardiac arrest. Overdose response must take the pathophysiology of opioid overdose into account. When someone experiences opioid overdose, regulation of breathing is impaired, respiration is depressed and insufficient oxygen reaches the brain and other organs.1 Because the person experiencing overdose is not breathing effectively, oxygen also cannot reach the heart and the individual may experience cardiac arrest (i.e., their heart stops beating or beats too ineffectively to support their vital organs).1" Ferguson M, Rittenbach K, Leece P, et al. Guidance on take-home naloxone distribution and use by community overdose responders in Canada. CMAJ. 2023;195(33):E1112-E1123. doi:10.1503/cmaj.230128 |

| 24. Rescue Breathing in Response to Overdose "Rescue breathing for persons suspected of having an opioid overdose has considerable support among harm reduction programs and in the medical literature.18 This preference is based on the physiology of an opioid overdose. Opioids suppress the autonomic respiratory response to declining oxygen saturation and rising carbon dioxide levels. If this response remains suppressed, the consequences are hypoxia, acidosis, organ failure and death. The majority, if not all, of the community-based naloxone programs in the United States train responders in a rescue breathing technique. In this technique, the nostrils of the unconscious individual are pinched closed, a seal is formed between the mouths of the victim and the responder, and breaths are introduced every five seconds by the responder. Further support for rescue breathing comes from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) in its Opioid Overdose Toolkit.19 In late 2014, WHO issued guidelines on community management of opioid overdose recommending, 'In suspected opioid overdose, first responders should focus on airway management, assisting ventilation and administering naloxone.'20 This was rated as a strong recommendation based on a weak quality of evidence." New York State Technical Working Group on Resuscitation Training in Naloxone Provision Programs: 2016 Report. New York State, Department of Health, AIDS Institute; 2016:16. |

| 25. Involvement of Fentanyl in Overdose Deaths in the US "Fentanyl was detected in 56.3% of 5,152 opioid overdose deaths in the 10 states during July–December 2016 (Figure). Among these 2,903 fentanyl-positive deaths, fentanyl was determined to be a cause of death by the medical examiner or coroner in nearly all (97.1%) of the deaths. Northeastern states (Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Rhode Island) and Missouri** reported the highest percentages of opioid overdose deaths involving fentanyl (approximately 60%–90%), followed by Midwestern and Southern states (Ohio, West Virginia, and Wisconsin), where approximately 30%–55% of decedents tested positive for fentanyl. New Mexico and Oklahoma reported the lowest percentage of fentanyl-involved deaths (approximately 15%–25%). In contrast, states detecting any fentanyl analogs in >10% of opioid overdose deaths were spread across the Northeast (Maine, 28.6%, New Hampshire, 12.2%), Midwest (Ohio, 26.0%), and South (West Virginia, 20.1%) (Figure) (Table 1). "Fentanyl analogs were present in 720 (14.0%) opioid overdose deaths, with the most common being carfentanil (389 deaths, 7.6%), furanylfentanyl (182, 3.5%), and acetylfentanyl (147, 2.9%) (Table 1). Fentanyl analogs contributed to death in 535 of the 573 (93.4%) decedents. Cause of death was not available for fentanyl analogs in 147 deaths.†† Five or more deaths involving carfentanil occurred in two states (Ohio and West Virginia), furanylfentanyl in five states (Maine, Massachusetts, Ohio, West Virginia, and Wisconsin), and acetylfentanyl in seven states (Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Mexico, Ohio, West Virginia, and Wisconsin). U-47700 was present in 0.8% of deaths and found in five or more deaths only in Ohio, West Virginia, and Wisconsin (Table 1). Demographic characteristics of decedents were similar among overdose deaths involving fentanyl analogs and fentanyl (Table 2). Most were male (71.7% fentanyl and 72.2% fentanyl analogs), non-Hispanic white (81.3% fentanyl and 83.6% fentanyl analogs), and aged 25–44 years (58.4% fentanyl and 60.0% fentanyl analogs) (Table 2). "Other illicit drugs co-occurred in 57.0% and 51.3% of deaths involving fentanyl and fentanyl analogs, respectively, with cocaine and confirmed or suspected heroin detected in a substantial percentage of deaths (Table 2). Nearly half (45.8%) of deaths involving fentanyl analogs tested positive for two or more analogs or fentanyl, or both. Specifically, 30.9%, 51.1%, and 97.3% of deaths involving carfentanil, furanylfentanyl, and acetylfentanyl, respectively, tested positive for fentanyl or additional fentanyl analogs. Forensic investigations found evidence of injection drug use in 46.8% and 42.1% of overdose deaths involving fentanyl and fentanyl analogs, respectively. Approximately one in five deaths involving fentanyl and fentanyl analogs had no evidence of injection drug use but did have evidence of other routes of administration. Among these deaths, snorting (52.4% fentanyl and 68.8% fentanyl analogs) and ingestion (38.2% fentanyl and 29.7% fentanyl analogs) were most common. Although rare, transdermal administration was found among deaths involving fentanyl (1.2%), likely indicating pharmaceutical fentanyl (Table 2). More than one third of deaths had no evidence of route of administration." Julie K. O’Donnell, PhD; John Halpin, MD; Christine L. Mattson, PhD; Bruce A. Goldberger, PhD; R. Matthew Gladden, PhD. Deaths Involving Fentanyl, Fentanyl Analogs, and U-47700 — 10 States, July–December 2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Vol. 66. Centers for Disease Control. October 27, 2017. |

| 26. American College of Medical Toxicology and the American Academy of Clinical Toxicology position statement: nalmefene should not replace naloxone as the primary opioid antidote at this time "As physicians, pharmacists, scientists, and specialists in poison information, we are experts in pharmacology, toxicology, and the management of opioid overdose and addiction. We applaud the effort to seek out new therapeutic strategies for the management of these patients. "We are concerned that the use of a longer-acting reversal agent would not improve on current practice and could potentially cause harm. When withdrawal is precipitated by an opioid antagonist, there are few good management options. In most cases, the best strategy is to address and support the patient’s signs and symptoms until the effects of the antagonist wane. In the case of naloxone, which has a relatively short duration of action, severe withdrawal usually lasts less than an hour with symptoms typically persisting no more than 90 min [Citation25–27]. A longer-acting antagonist is anticipated to cause longer-lasting precipitated withdrawal and may lead to worse patient outcomes. Clinical experience with both naltrexone and nalmefene suggests prolonged withdrawal is a complication of longer-acting opioid antagonists [Citation28]. Although a longer-acting antagonist may be theoretically beneficial for the resuscitation of opioid-naive individuals in an opioid-induced mass casualty incident, this type of event has never been reported in North America and this application is unstudied. "We are also concerned that patients who receive nalmefene may require longer periods of observation, by up to several hours, to observe for recrudescent effects as the antagonist effects wane. Patients who receive nalmefene will still need medical observation to ensure that respiratory depression does not recur after the effects of the medication subside. This will prolong emergency department visit length and challenge patient and clinician expectations, further burdening a taxed system. Further clinical study is needed to understand whether a reduction in repeat antagonist use justifies a longer length of stay or longer period of withdrawal. "Finally, we are concerned that intranasal nalmefene has not been adequately studied for effectiveness in the actual setting and patient population: for patients with severe opioid intoxication in the out-of-hospital environment. Lack of proof of safety and efficacy in real-world use could result in significant harm if widely utilized. "The potential benefits of nalmefene over naloxone (greater opioid receptor affinity, longer duration action) carry the risk of causing harm. These benefits, if present, should be demonstrated in the clinical environment, balanced with the risks, and compared to naloxone prior to the broad adoption of nalmefene." Andrew I. Stolbach, Maryann E. Mazer-Amirshahi, Lewis S. Nelson & Jon B. Cole (2023) American College of Medical Toxicology and the American Academy of Clinical Toxicology position statement: nalmefene should not replace naloxone as the primary opioid antidote at this time, Clinical Toxicology, 61:11, 952-955, DOI: 10.1080/15563650.2023.2283391 |

| 27. Naloxone vs Nalmefene "While the addition of stronger, longer-acting opioid overdose reversal agents expands the options available to combat the fatal opioid overdose crisis, their inception is perhaps without clinical grounds. Data supports continued practice without these stronger, longer acting nalmefene agents, and it is unclear whether any benefits nalmefene offers outweigh the apparent risks of its use. Nalmefene may yet find a clinical niche, but at this time, appears to be a solution designed to resolve hypothetical complications without fully understanding the unintended consequences of use. As such, without further evidence healthcare professionals should not support the use of stronger, longer-acting opioid overdose reversal agents. Further study is necessary, before nalmefene, or other naloxone alternatives should be incorporated into general practice." Infante AF, Elmes AT, Gimbar RP, Messmer SE, Neeb C, Jarrett JB. Stronger, longer, better opioid antagonists? Nalmefene is NOT a naloxone replacement. Int J Drug Policy. 2024;124:104323. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2024.104323 |

| 28. Xylazine is a Kappa-Opioid Agonist with Gender-Specific Responses to Opioid Antagonists (e.g. Naloxone) "Here, we report the first xylazine dose-response locomotor study in male and female mice as well as the first assessment of adrenergic- and opioid-receptor antagonist-precipitated withdrawal symptoms following, xylazine, fentanyl, and xylazine/fentanyl administration in mice. These experiments show that male and female mice are differentially sensitive to xylazine. We find female mice are less sensitive to the motor-suppressing effects of xylazine contrary to the recent findings in rats reported by Khatri et al. (2023), potentially due to their use of repeated dosing of xylazine or species differences [27]. Using a modified version of our 3-day precipitated withdrawal model [40,41,46], we show xylazine is indeed responsive to naloxone, contrary to common assumptions made by both health professionals and in the media [7]. Both sexes exhibited some level of somatic withdrawal behaviors to xylazine and naloxone, though females showed sensitized behavioral responding. Indeed, females appear to be as sensitive, if not more sensitive to xylazine withdrawal than fentanyl withdrawal at tested doses, while males remain much more responsive to fentanyl withdrawal conditions. At the doses tested in our study, the effect of naloxone precipitated withdrawal on xylazine/fentanyl combination was synergistic as compared to each drug in isolation. This was especially apparent when examining increased bouts of paw tremors, which may represent a more passive coping behavior that we have previously observed is sexually dimorphic in opioid withdrawal [41]. In contrast, we did not observe similar findings when withdrawal was precipitated by atipamezole, an α2-AR antagonist used anesthesia reversal in veterinary medicine. These intriguing findings led us to consider the possibility of direct xylazine activity on opioid receptors. Previous studies have shown that xylazine is antinociceptive, results in a cross-tolerance to some mechanisms of opioid induced antinociception, and that these effects are naloxone-sensitive, but surprisingly not sensitive to the κOR selective antagonist nor-BNI [57–60]. Congruent with this data, we did not observe significant expression of withdrawal behavior to nor-BNI precipitated withdrawal, and pretreatment with nor-BNI exacerbated naloxone precipitated withdrawal in female mice. Until now, xylazine was thought to exert these effects through promotion of endogenous opioid release and xylazine has not been directly tested as a potential opioid agonist. We are the first to report definitive evidence that xylazine acts as a full agonist at κOR and is biased towards G-protein signaling pathways." Bedard ML, Huang XP, Murray JG, et al. Xylazine is an agonist at kappa opioid receptors and exhibits sex-specific responses to opioid antagonism. Addict Neurosci. 2024;11:100155. doi:10.1016/j.addicn.2024.100155 |

| 29. Nalmefene vs Naloxone "As shown above, the data supports that these stronger, longer-acting agents may be unnecessary, with other research suggesting their existence may also cause undue harm. Using a stronger or longer-acting antagonist as a one-size-fits-all approach may put patients at greater risk for experiencing more severe and/or prolonged withdrawal symptoms.(Bennett et al., 2020; Hill et al., 2022; Neale & Strang, 2015) Providers may find it difficult to manage withdrawal symptoms and comorbidities like chronic pain, forcing the patient to suffer until the reversal agent wears off. It is also notable to consider how patients who are naïve to nalmefene may react upon discharge following administration. These patients may attempt to self-manage withdrawal symptoms or cravings only to find higher opioid doses are required to overcome the nalmefene blockade, increasing their propensity to overdose as was observed when patients began adjusting to naloxone.(Neale & Strang, 2015) Alternatively, patients accustomed to opioid withdrawal symptoms subsiding within 1 to 2 h after naloxone administration may not be able to tolerate several hours of withdrawal, increasing both the likelihood of attempts to overcome the blockade and resistance to using reversal agents in the future.(Neale & Strang, 2015) Considering the average layperson likely does not fully grasp the potential harm of nalmefene, and that any opioid overdose education they may have received from an opioid overdose education & naloxone distribution (OEND) program would have been naloxone and harm reduction focused, adding these agents into the market creates opportunities for greater clinical complication. This lack of familiarity combined with the lack of clinical discretionary knowledge by the layperson who may be administering these medications in the field sets the stage for nalmefene exposure to elicit prolonged agitation and negative consequences.(Brenner et al., 2021) Furthermore, it is possible that nalmefene administration may complicate the initiation of medications for opioid use disorder such as buprenorphine/naloxone, which can be done in as little as three hours following the last opioid use when co-administered with naloxone.(Randall et al., 2023) Additionally, the FDA approved intranasal naloxone for over-the-counter use in March 2023. It is yet to be seen how this will affect its insurance coverage and medication access.(Harris, 2023b) This may especially affect vulnerable patient populations such as those with limited disposable income. Coverage for prescription nalmefene may serve some relief when naloxone is not covered or attainable by other means." Infante AF, Elmes AT, Gimbar RP, Messmer SE, Neeb C, Jarrett JB. Stronger, longer, better opioid antagonists? Nalmefene is NOT a naloxone replacement. Int J Drug Policy. 2024;124:104323. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2024.104323 |

| 30. Xylazine and Overdoses "Xylazine is a non-opiate sedative, analgesic, and muscle relaxant that shares its drug class (α2-adrenoreceptor agonists) with medications such as clonidine, lofexidine, tizanidine, and dexmedetomidine [6]. It was initially developed as an antihypertensive agent by Farbenfabriken Bayer AG in 1962; however, subsequent testing revealed severe adverse events related to hypotension and central nervous system (CNS) depression [6, 7]. Consequently, xylazine never gained approval for human use; however, it was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1972 exclusively for use in veterinary medicine [6, 7]. At present, xylazine remains unregulated under both the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) in the USA [8] and the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (CDSA) in Canada [9]. "Fatal xylazine-positive overdoses, often co-occurring with synthetic compounds such as IMF and its analogs, surged dramatically in the past decade in North America. These overdoses have increased approximately 12-fold between 2018 and 2021 in the USA [6]. Importantly, naloxone—an opioid antagonist medication that is safe and effective for reversing opioid-induced respiratory depression during overdose—does not directly address the effects of xylazine as it is not an opioid, thereby introducing new challenges regarding overdose response best practices within clinical- and community-based settings [8, 10]. Altogether, this pressing issue has prompted The White House Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) to designate fentanyl associated or adulterated with xylazine (FAAX) as an emergent health threat to the USA in April 2023 and issue a comprehensive response plan in July 2023 [11, 12]. Similar cases are also on the rise in Canada and other countries such as the UK, marking the first xylazine-involved overdose outside of North America [9, 13]. Against the backdrop of this global health crisis, it is imperative to renew efforts in delivering evidence-based public health and harm reduction programs to facilitate secondary and tertiary prevention of adverse health outcomes following xylazine exposure." Zhu DT. Public health impact and harm reduction implications of xylazine-involved overdoses: a narrative review. Harm Reduct J. 2023;20(1):131. Published 2023 Sep 12. doi:10.1186/s12954-023-00867-x |

| 31. Safe Supply and Non-Fatal Overdose "In this study involving 47 individuals who were admitted to an unsanctioned compassion club, we found that enrolment in the program was associated with a reduction in any type of non-fatal overdose as well as non-fatal overdose involving naloxone administration. These findings, suggesting that enrollment in DULF's intervention likely decreased overdose rates, appear to be amongst the first in a growing body of research on the impacts of a safer drug supply that does not employ the medical system. "Our findings are aligned with previous evaluations of safer supply programs that have found positive outcomes associated with program engagement, as well as the findings of the scoping review of safer supply programs published in this issue (Ledlie et al. 2024). A previous quantitative study investigating a medicalized and prescriber-based model of safer supply found that enrolment in such programming reduced use of emergency departments, hospital admissions and healthcare costs (Gomes et al., 2022). In addition, several qualitative investigations of safer supply programs, involving prescriber- and vending machine-based programs, have found that such programs help reduce illicit drug use, overdose risk, and led to other improvements in health, social and financial well-being (Bardwell, Ivsins, Mansoor, Nolan, & Kerr, 2023; Ivsins, Boyd, Beletsky, & McNeil, 2020; Ivsins, Boyd, Mayer, et al., 2020; Ivsins et al., 2021; Ledlie et al. 2024; Schmidt et al., 2023). Perhaps most relevant to the current study, a recent quantitative study of a prescriber-based opioid safer supply program in Toronto reported an 80% reduction in non-fatal overdose among participants after 8 months of program engagement (Nefah et al, 2023). However, such programs are known to often suffer from low enrolment and retention rates, attributed in part to inability of such programs to accommodate a large number of individuals and a lack of desirable options and dose for people who use drugs (May, Holloway, Buhociu, & Hills, 2020). This problem may be further compounded by the medical system's inability to prescribe or allow access to illegal drugs (Tyndall, 2020). This in turn has prompted calls for the implementation of more community-based compassion club models operating outside of the medical system as a means of increasing access to safer supply (Thomson et al., 2019). Indeed, some physician leaders have expressed that they would rather not to be responsible for ensuring access to safer supply given the associated ethical issues and the current state of the overburdened healthcare system (Bach, 2022). Our study contributes to the existing literature by describing the impact of a non-medicalized safer supply program on non-fatal overdose. "People who use drugs, and other experts in the field, have long expressed a demand for a stable, predictable, and easy to access supply of drugs to prevent overdose in the context of the current overdose crisis (Bonn et al., 2020; Health Canada, 2023a; BC Coroners Service, 2023a; Tyndall, 2020). Despite its limited scope, this study has implications for research and policy development specific to safer supply and overdose prevention. The lack of active studies in the field of de-medicalized safer supply distribution highlights the need for more research. Given the recent arrest of DULF's co-founders (Greer, 2023), pathways for exemptions to Canada's Controlled Drugs and Substances Act are needed to enable institutions to run programs and track relevant statistics that can assist policymakers in making decisions (Bonn et al., 2021), as well as revisions to existing policy frameworks, specifically the Special Access Program, the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act, and Food and Drugs Act, which limit the implementation of compassion clubs as a response to Canada's public health crisis (Bonn et al., 2021). This policy hurdle is further compounded by a lack of available licit substances for such a program; there are currently no appropriate approved drugs in Canada's Drug Product Database (Health Canada, 2023b). This further underscores the need for policy changes that facilitate a deeper understanding of the effectiveness of compassion clubs as a means of optimizing support for individuals who are at risk of overdose. Further, additional prospective study of effectiveness is needed, alongside qualitative studies focused on implementation issues and cost-effectiveness research to further uncover the impacts and limitations of this unique approach to safe supply programming." Jeremy Kalicum, Eris Nyx, Mary Clare Kennedy, Thomas Kerr, The impact of an unsanctioned compassion club on non-fatal overdose, International Journal of Drug Policy, 2024, 104330, ISSN 0955-3959, doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2024.104330. |

| 32. Association of Dose Tapering With Overdose or Mental Health Crisis "In the current study, tapering was associated with absolute differences in rates of overdose or mental health crisis events of approximately 3 to 4 events per 100 person-years compared with nontapering. These findings suggest that adverse events associated with tapering may be relatively common and support HHS recommendations for more gradual dose reductions when feasible and careful monitoring for withdrawal, substance use, and psychological distress.9 "Previous research has examined adverse outcomes associated with discontinuing long-term opioids.10-14 This analysis demonstrated associations between adverse outcomes and a more sensitive indicator of opioid dose reduction (≥15% from baseline). The associations persisted in sensitivity analyses that excluded patients who discontinued opioids during follow-up, suggesting that the observed associations between tapering and overdose and mental health crisis are not entirely explained by events occurring in patients discontinuing opioids. Additionally, all categories of maximum dose reduction velocity demonstrated higher relative rates of outcomes compared with the lowest (<10% per month), suggesting that risks were not confined to patients undergoing rapid tapering. "Patients undergoing tapering from higher baseline opioid doses had higher associated risk for the study outcomes compared with patients undergoing tapering from lower baseline doses. Due to physiologic opioid tolerance,27 patients receiving higher doses may have heightened intolerance of opioid dose disruption, potentially warranting additional caution in patients tapering from higher doses." Agnoli A, Xing G, Tancredi DJ, Magnan E, Jerant A, Fenton JJ. Association of Dose Tapering With Overdose or Mental Health Crisis Among Patients Prescribed Long-term Opioids. JAMA. 2021;326(5):411–419. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.11013 |

| 33. Polydrug Involvement in Pharmaceutical Overdose Deaths in the US "Opioids were frequently implicated in overdose deaths involving other pharmaceuticals. They were involved in the majority of deaths involving benzodiazepines (77.2%), antiepileptic and antiparkinsonism drugs (65.5%), antipsychotic and neuroleptic drugs (58.0%), antidepressants (57.6%), other analgesics, antipyretics, and antirheumatics (56.5%), and other psychotropic drugs (54.2%). Among overdose deaths due to psychotherapeutic and central nervous system pharmaceuticals, the proportion involving only a single class of such drugs was highest for opioids (4903/16 651; 29.4%) and lowest for benzodiazepines (239/6497; 3.7%)." Christopher M. Jones, PharmD, Karin A. Mack, PhD, and Leonard J. Paulozzi, MD, "Pharmaceutical Overdose Deaths, United States, 2010," Journal of the American Medical Association, February 20, 2013, Vol 309, No. 7, p. 658. |

| 34. Xylazine-Involved Deaths "Xylazine, an alpha-2 receptor agonist, is used in veterinary medicine as a sedative and muscle relaxant; it is not approved for use in humans. However, reports of adulteration of illicit opioids with xylazine have been increasing in the United States (1–3). In humans, xylazine can cause respiratory depression, bradycardia, and hypotension (4). Typical doses of naloxone are not expected to reverse the effects of xylazine; therefore, persons who use xylazine-adulterated opioids are at high-risk for fatal overdose. Although some regions of the United States have reported increases in xylazine-involved deaths, xylazine was involved in <2% of overdose deaths nationally in 2019 (2,5). Most xylazine-involved deaths are associated with fentanyls, including fentanyl analogs (1,5)." Chhabra, N., Mir, M., Hua, M. J., Berg, S., Nowinski-Konchak, J., Aks, S., Arunkumar, P., & Hinami, K. (2022). Notes From the Field: Xylazine-Related Deaths - Cook County, Illinois, 2017-2021. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 71(13), 503–504. doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7113a3 |

| 35. Changes Demographics, Number, and Substance Involved in Drug Overdoses in the US 1979-2016 "The overall mortality rate for unintentional drug poisonings in the United States grew exponentially from 1979 through 2016. This exponentially increasing mortality rate has tracked along a remarkably smooth trajectory (log linear R2 = 0.99) for at least 38 years (left panel). By contrast, the trajectories of mortality rates from individual drugs have not tracked along exponential trajectories. Cocaine was a leading cause in 2005–2006, which was overtaken successively by prescription opioids, then heroin, and then synthetic opioids such as fentanyl. The demographic patterns of deaths due to each drug have also shown substantial variability over time. Until 2010, most deaths were in 40- to 50-year old persons, from cocaine and increasingly from prescription drugs. Deaths from heroin and then fentanyl have subsequently predominated, affecting younger persons, ages 20 to 40 (middle panel). Mortality rates for males have exceeded those for females for all drugs. Rates for whites exceeded those for blacks for all opioids, but rates were much greater among blacks for cocaine. Death rates for prescription drugs were greater for rural than urban populations. The geographic patterns of deaths also vary by drug. Prescription opioid deaths are widespread across the United States (right panel), whereas heroin and fentanyl deaths are predominantly located in the northeastern United States and methamphetamine deaths in the southwestern United States. Cocaine deaths tend to be associated with urban centers." Hawre Jalal, et al. Changing dynamics of the drug overdose epidemic in the United States from 1979 through 2016. Science, Sept. 21, 2018. Vol. 361, Issue 6408, eaau1184. DOI: 10.1126/science.aau1184. |

| 36. Growth of Xylazine in US Drug Market "We summarize longitudinal, recent, and geographically specific evidence describing how xylazine is increasingly implicated in overdose deaths in jurisdictions spanning all major US regions and link it to detailed ethnographic observations of its use in Philadelphia open-air narcotics markets. Xylazine presence in overdose deaths grew exponentially during the observed period, rising nearly 20-fold between 2015 and 2020. Whereas the most recent national data from the State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System characterized the level of xylazine-present overdoses in 2019 (Kariisa, 2021), we found that the prevalence increased by nearly 50% from 2019 to 2020 alone, indicating a need for more recent data to guide the public health response. Furthermore, we find that even looking at only 10 jurisdictions a greater number of xylazine-present overdose deaths were seen in 2020 (854), than the previous study looking at 38 states in 2019 (826) (Kariisa, 2021), implying a very fast rate of growth nationally. "Xylazine prevalence was observed earliest and at the highest magnitude in the Northeast, and may be spreading west, in a pattern similar to the trajectory of illicitly-manufactured fentanyls in recent years (Shover et al., 2020). This similarity may not be incidental, as an analysis of the co-occurrence of fentanyl and xylazine indicates a strong ecological link, with fentanyl nearly universally implicated in xylazine-present overdose deaths. Further, ethnographic data among PWID suggests that the use of xylazine as an illicit drug additive may predominantly serve as a response to the short duration of fentanyl. By ‘giving fentanyl legs’—offering improved duration of effect—the addition of xylazine may confer a competitive market advantage for illicit opioid formulations that contain it, as it remedies one of the most commonly expressed complaints that PWID hold regarding fentanyl-based street opioid formulations." Friedman, J., Montero, F., Bourgois, P., Wahbi, R., Dye, D., Goodman-Meza, D., & Shover, C. (2022). Xylazine spreads across the US: A growing component of the increasingly synthetic and polysubstance overdose crisis. Drug and alcohol dependence, 233, 109380. doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2022.109380. |

| 37. Deaths from Drug Overdose in the United States in 2015 "During 2015, drug overdoses accounted for 52,404 U.S. deaths, including 33,091 (63.1%) that involved an opioid. There has been progress in preventing methadone deaths, and death rates declined by 9.1%. However, rates of deaths involving other opioids, specifically heroin and synthetic opioids other than methadone (likely driven primarily by illicitly manufactured fentanyl) (2,3), increased sharply overall and across many states." Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, Scholl L. Increases in Drug and Opioid-Involved Overdose Deaths — United States, 2010–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65:1445–1452. |

| 38. Xylazine-Involved and Xylazine-Associated Deaths in Cook County, IL "A xylazine-associated death was defined as a positive postmortem xylazine serum toxicology test result in an unintentional, undetermined, or pending intent substance-related death during January 2017–October 2021. Routine postmortem tests were conducted for other substances including fentanyl, fentanyl analogs, cocaine, and naloxone. Xylazine testing is standard in Cook County for suspected drug overdose deaths. This activity was reviewed by CDC and was conducted consistent with applicable federal law and CDC policy.* "A total of 236 xylazine-associated deaths were reported during the study period. Xylazine-associated deaths increased throughout the study period; incidence peaked during July 2021 (Figure). The percentage of fentanyl-associated deaths involving xylazine also increased throughout the study period, rising to a peak of 11.4% of fentanyl-related deaths assessed by the Cook County Medical Examiner’s Office during October 2021. Fentanyl or fentanyl analogs were detected on forensic testing in most xylazine-involved deaths (99.2%). Other common co-occurring substances included diphenhydramine (79.7%), cocaine (41.1%), and quinine (37.3%). Naloxone was detected in 32.2% of xylazine-associated deaths." Chhabra, N., Mir, M., Hua, M. J., Berg, S., Nowinski-Konchak, J., Aks, S., Arunkumar, P., & Hinami, K. (2022). Notes From the Field: Xylazine-Related Deaths - Cook County, Illinois, 2017-2021. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 71(13), 503–504. doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7113a3 |

| 39. Receipt of Opioid Use Disorder Treatments Prior to Fatal Overdoses and Comparison to No Treatment "The findings revealed that exposures to MOUD, even if not continued throughout the six-month exposure period was associated with reduced risk of a fatal poisoning compared to non-MOUD forms of treatment and no treatment exposure. It is also clear that risk of death associated with exposure to non-MOUD forms of treatment was no less than that for no treatment; indeed, non-MOUD treatment might have produced worse outcomes than no treatment. Comparing the relative risk for the treatments for which agency-based numbers are available revealed that any exposure to methadone in the six months prior to death in 2017 was associated with 65% reduced relative risk of fatal opioid poisoning compared to exposure to any non-MOUD treatment recorded in the DMHAS database. Even more apparent, based on the available data from 2017, the relative risk of fatal opioid death in the six months following exposure to non-MOUD treatments ranged from 1.5 to 1.74 compared to no treatment. This is an unacceptably high probability for treatments that are purported to benefit patients with OUD and likely to be paid for by public tax revenues. In fact, it seems likely, based on our estimates of the number of people with OUD not exposed to treatment, that non-MOUD treatments were inferior to no treatment. "There is a century of data demonstrating that non-MOUD treatment is followed by a high rate of relapse to opioid use – especially for morphine and heroin – approaching 90% at six months (Musto, 1999, Broers et al., 2000, Heimer et al., 2019). Relapse rates for those regularly using fentanyl may be even higher (Stone et al. 2018). There is ample evidence from the U.S. and elsewhere that longer-term non-MOUD treatments place those who relapse at an especially high risk of opioid overdose and death.(Strang, Beswick and Gossop, 2003; Wakeman et al. 2020). There is also compelling evidence that agonist MOUD decreases opioid-involved and all-cause mortality (Santo et al. 2021), and nearly thirty years of evidence that methadone reduces HIV-related mortality (Fugelstad et al., 1995, Parashar et al., 2016, Sordo et al., 2017). Our analysis was based on exposures to treatment, not their completion or retention, therefore our findings indicate that exposures to agonist MOUD treatment convey more benefit that non-MOUD even if the treatment is incompletely adhered to or terminated." Robert Heimer, Anne C. Black, Hsiuju Lin, Lauretta E. Grau, David A. Fiellin, Benjamin A. Howell, Kathryn Hawk, Gail D’Onofrio, William C. Becker, Receipt of Opioid Use Disorder Treatments Prior to Fatal Overdoses and Comparison to No Treatment in Connecticut, 2016-17, Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 2023, 111040, ISSN 0376-8716, doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2023.111040. |

| 40. Prescription Opioid Tapering, Overdose Risk, and Suicidality "In this emulated trial including more than 400 000 episodes of stable long-term opioid therapy, opioid tapering was associated with a small (0.15%) absolute increase in the risk of overdose or suicide events compared with a stable dosage during 11 months of follow-up. We did not identify a difference in the risk of overdose or suicide events between abrupt discontinuation and stable dosage, although the smaller number of episodes categorized as abrupt discontinuation may have reduced precision. The findings were robust to secondary and sensitivity analyses. "The risk ratio of 1.15 for opioid overdose or suicide events associated with opioid tapering was smaller than in past studies conducted in other populations. This study examined commercially insured individuals receiving a stable long-term opioid dosage without evidence of opioid misuse. A large study of Veterans Health Administration patients estimated adjusted hazard ratios between 1.7 and 6.8 for the association of treatment discontinuation with suicide or overdose among patient subgroups defined by length of prior treatment.17 A study of Oregon Medicaid recipients found adjusted hazard ratios for suicide of 3.6 for discontinuation and 4.5 for tapering.18 A study using the same claims data set and similar definition of long-term opioid therapy as our study identified effect estimates between those in our study and those in prior studies, with an estimated adjusted incidence rate ratio of 1.3 for the association of dose tapering with overdose and 2.4 for the association of dose tapering with suicide attempts.32" Larochelle MR, Lodi S, Yan S, Clothier BA, Goldsmith ES, Bohnert ASB. Comparative Effectiveness of Opioid Tapering or Abrupt Discontinuation vs No Dosage Change for Opioid Overdose or Suicide for Patients Receiving Stable Long-term Opioid Therapy. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(8):e2226523. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.26523 |

| 41. Trends in Drug Overdose Mortality in the US 2000-2019 "The number of accidental drug overdose deaths increased by 622% between 2000 and 2020, and age-standardized mortality rates increased nearly four-fold in both men and women. Age-period-cohort decomposition found rapid increases in mortality since 2012 in men and women, with higher mortality risk in cohorts born after 1990. The fastest increase occurred in Black Americans since 2012, and Americans of all races born after 1975 had significantly higher mortality risk, with mortality risk increasing rapidly in more recent cohorts. The peak of mortality has shifted from the 40–59 age group to the 30–40 year age group in the past decade." Fujita-Imazu, S., Xie, J., Dhungel, B., Wang, X., Wang, Y., Nguyen, P., Khin Maung Soe, J., Li, J., & Gilmour, S. (2023). Evolving trends in drug overdose mortality in the USA from 2000 to 2020: an age-period-cohort analysis. EClinicalMedicine, 61, 102079. doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.102079 |

| 42. Deaths in the UK Due to a Toxic Drug Supply and Drug Overdose "In 2020 drug related deaths in the United Kingdom (UK) reached the highest rate in over 25 years (ONS, 2021). Data between 2001-2018 evidences a substantial increase in drug poisonings over time for people who use opioids, with risk increasing particularly between the years of 2010-2018, an effect which was not entirely explained by the ageing of this cohort (Lewer et al., 2022). The concentration of drug related deaths are geographically varied in the UK. Areas of high economic deprivation, such as North-East England have more than three times the rate of drug related deaths than London (ONS, 2021). In the North East town of Middlesbrough citizens are statistically more likely to die from a drug related deaths than a car accident (Middlesbrough Council, 2020). Poverty, homelessness, an aging population of opioid users, unemployment, polydrug use and significant funding reductions for drug treatment services have been posited as contributing factors (ACMD, 2017; Lewer et al., 2022; ONS, 2019a, 2019b; Public Health England, 2018). The largest proportion of drug related deaths in the North-East of England are reported among men who are dependent on illicit opioids, such as heroin (ONS, 2022). The high prevalence of opioid usage in Middlesbrough combined with an unregulated and toxic illicit street tablet market (substances such as z-drugs, benzodiazepine and gabapentinoids) provides a potentially fatal risk environment due to interactions between these depressant drugs, which can significantly increase risk of drug related deaths (Akhgari, Sardari-Iravani, & Ghadipasha, 2021; Ford & Law, 2014; ONS, 2021, 2022)." Poulter, H. L., Walker, T., Ahmed, D., Moore, H. J., Riley, F., Towl, G., & Harris, M. (2023). More than just 'free heroin': Caring whilst navigating constraint in the delivery of diamorphine assisted treatment. The International journal on drug policy, 116, 104025. doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2023.104025 |

| 43. Growing Involvement of Xylazine in Deaths Due to a Toxic Drug Supply and Overdose "In overdose data from 10 jurisdictions – representing all four major US census regions – xylazine was found to be increasingly present in overdose mortality (Fig. 1). The highest prevalence was observed in Philadelphia, (with xylazine present in 25.8% of overdose deaths in 2020), followed by Maryland (19.3% in 2021) and Connecticut (10.2% in 2020). In 2021, xylazine prevalence also grew substantially in Jefferson County, Alabama, reaching 8.4% of overdose fatalities. Across the four census regions, the Northeast had the highest prevalence, and the West had the lowest (Fig. 2), with only six xylazine-present overdose deaths in total detected in Phoenix, Arizona, and 1 in San Diego County, California. Across jurisdictions, a clear increasing trend was noted. Pooling data for 2015, a total xylazine prevalence of 0.36% was observed. By 2020, this had grown to 6.7% of overdose deaths, representing a 20-fold increase. From 2019–2020 – the last year of data available for all jurisdictions – the prevalence increased by 44.8%." Friedman, J., Montero, F., Bourgois, P., Wahbi, R., Dye, D., Goodman-Meza, D., & Shover, C. (2022). Xylazine spreads across the US: A growing component of the increasingly synthetic and polysubstance overdose crisis. Drug and alcohol dependence, 233, 109380. doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2022.109380. |